Interpreters everywhere!

Last month, I was thrilled to have the chance to give a colloquium talk, “Interpreters everywhere!”, at the Indiana University Computer Science Colloquium!

This talk wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for my amazing students. In fact, some parts of it are directly ripped off from talks that my students Gan Shen and Jonathan Castello have given previously on our work: check out Gan’s talk on HasChor from ICFP 2023 and Jonathan’s talk on causal separation diagrams from OOPSLA 2024. It was shortly after Jonathan’s OOPSLA talk in 2024 that I realized that those two projects, which I hadn’t really thought of as having much in common, were really both about interpretation.

So a year later, when I was invited to give a talk at IU – which was the very place where I got hooked on PL via interpreters, back in 2008 when I started grad school – the choice of what to talk about was clear! The rest of this post is more or less a transcript of my talk, not including the Q&A at the end or the lovely introduction by Carlo Angiuli. Those parts, however, are included in the video recording, which you can find on YouTube if you’re interested!

Introduction

I’m so happy to be giving this talk, so thank you, Carlo, for hosting, and for that lovely introduction. I am going to talk about research, but this is much more than just a routine research talk; there is personal significance for me to be giving this particular talk to this particular audience, and I am only sorry that I couldn’t be there in person to visit Bloomington, where it’s so beautiful in the fall.

I’m going to begin, as I so often do, with a little bit of storytelling to set the stage. And the story has to begin with Dan.

I was a PhD student here at IU from 2008 to 2014, and when I arrived in 2008, I took Dan Friedman’s programming languages course, which was fondly known as “Intro to Dan”. In this course, you learn about what programming languages are made of by writing interpreters. So that was how my PhD began, and it was how I got hooked on programming languages as a field.

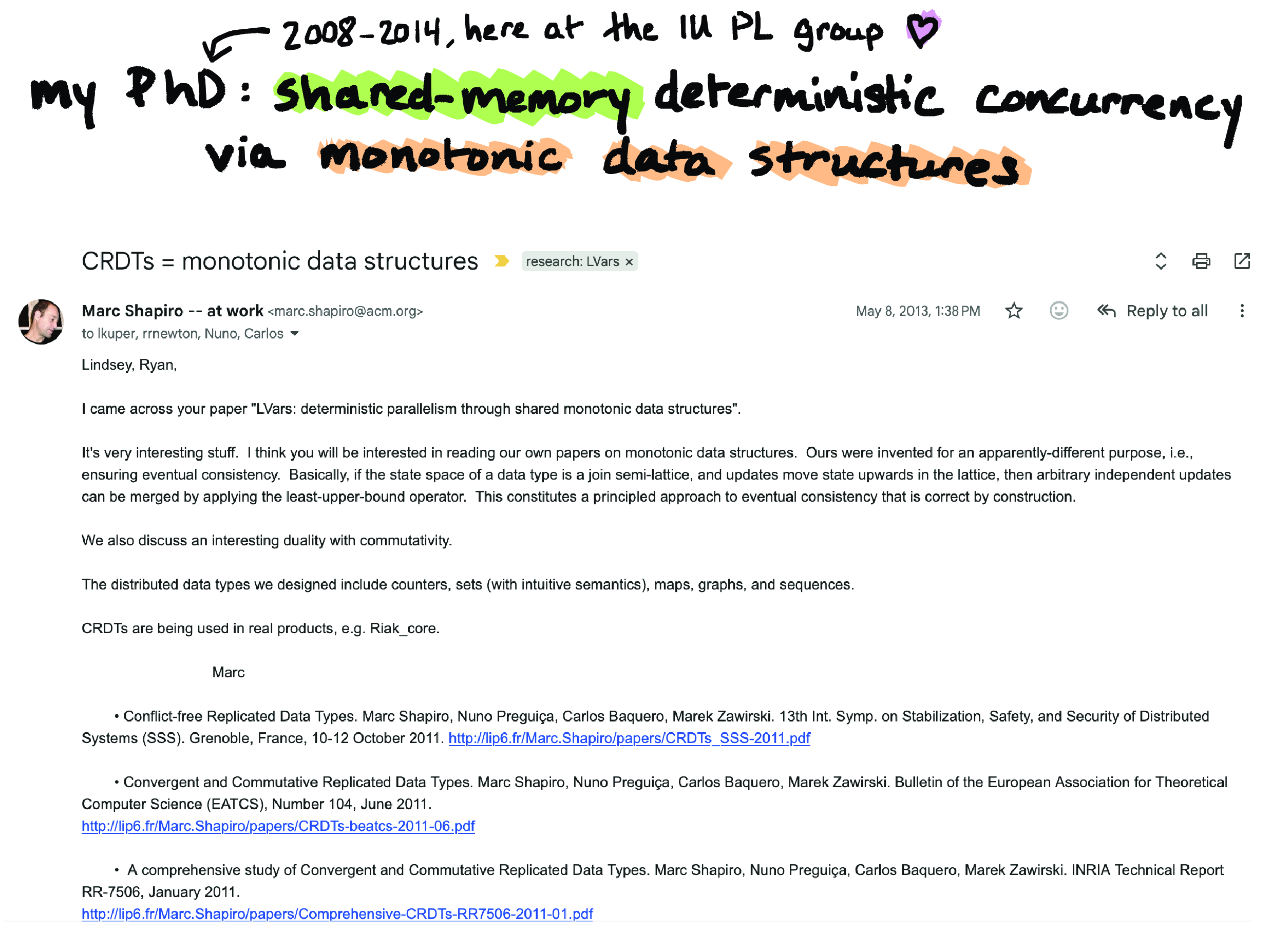

I was at Indiana for six years doing a PL PhD, and that journey involved a lot of twists and turns that would be enough for a whole other talk. But, long story short, eventually I was working with my advisor, Ryan, on programming language abstractions for writing shared-memory deterministic concurrent programs. And we published some papers about this line of work, using what we called monotonic data structures.

And it was all about shared memory – or so I thought. But then, in the last year or so of my PhD, people who were interested in distributed computing – so, specifically not shared memory – tracked me down and said, “Hey, your work seems to have a lot to do with our work. You really ought to read our work.”

As an example of that, here’s an email I got in 2013 from Marc Shapiro. He’s a well-known distributed systems researcher, and he’s one of the inventors of something called conflict-free replicated data types, or CRDTs, which are data structures that are used in distributed systems to ensure fault tolerance and high availability. So I got this email from Marc near the end of my PhD, and you don’t have to read this, but this is essentially pointing out that I ought to be paying attention to his and his collaborators’ work on CRDTs, ‘cause it had a lot to do with my work. And it turned out, of course, they were right.

Of course, to make sense of CRDTs, I had to do some background reading on distributed systems, and one thing kind of led to another, and, you know, when I started looking at the papers that these folks were recommending to me, it was kind of a revelation for me, since up until then, I had only really paid attention to programming languages as a subfield, and I didn’t really look beyond PL research to consider everything else out there.

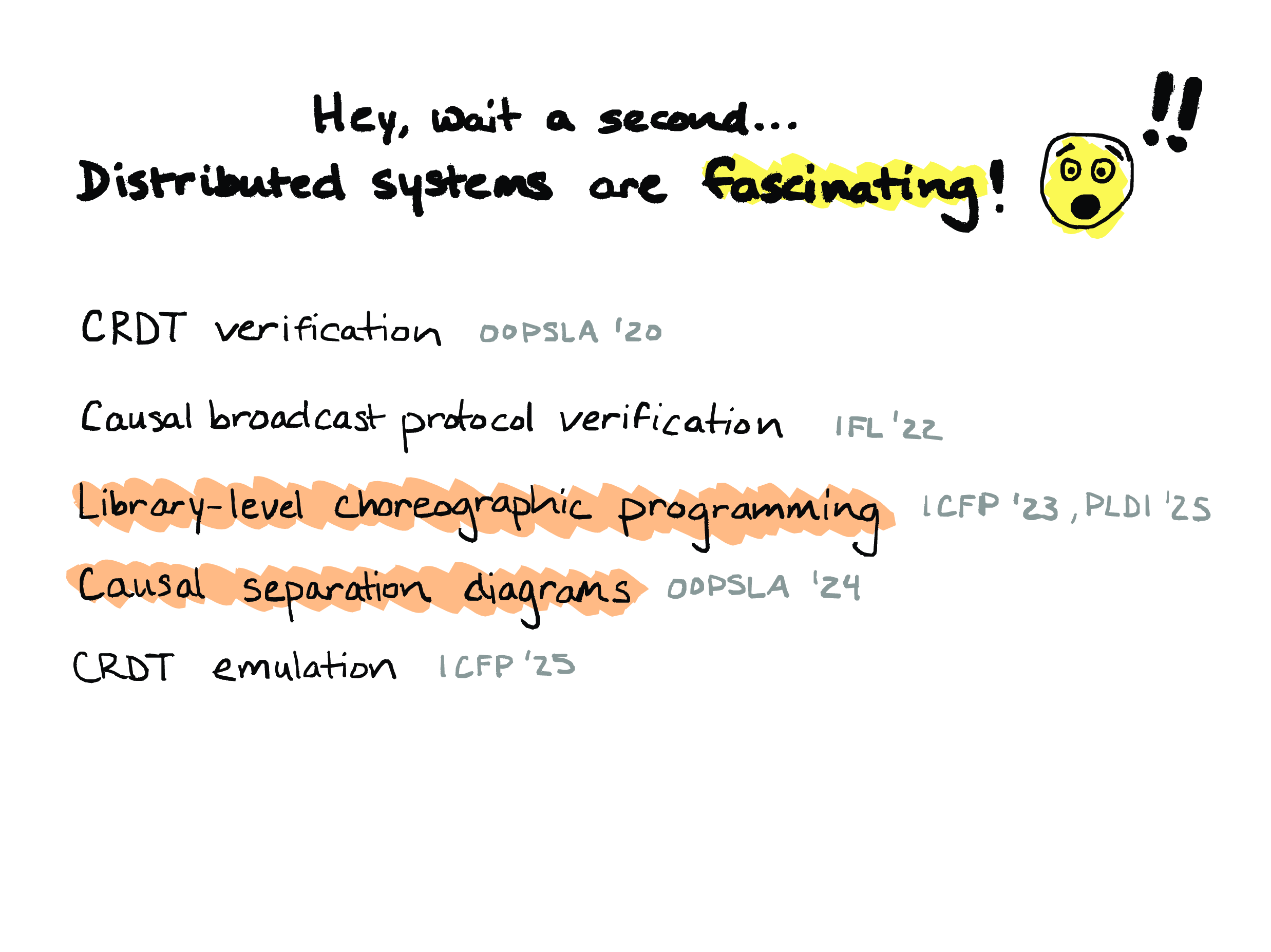

But once I did finally look beyond PL, I realized: Wait a second! Distributed systems are actually fascinating! And the field of distributed computing is something that I had a lot to learn from. Not only is it immediately practically relevant to our work and our lives, but it’s also full of profound and beautiful results. And so that’s when I really began to study distributed systems.

Of course, I haven’t stopped being a PL person; PL is still my research home. But for these last, you know, ten to fifteen years, I’ve attempted to study distributed systems from a PL person’s point of view. I was going pretty slowly at first, but this learning process accelerated quite a bit when I got a job at UC Santa Cruz in 2018, and I was suddenly expected to teach distributed systems courses, so at that point it really meant I couldn’t fake it anymore; I had to actually deeply understand something about distributed systems, instead of being a dilettante like I had been up until then. And that in turn influenced what research problems I was interested in. So, these last several years, that’s mostly where my mind has been, research-wise, and my students and I have been going around sneaking distributed systems papers into PL conferences. These papers listed here are a few examples from the last six years, a couple of which I’ll say more about later.

But finally, then, after many years of this, at some point recently I had another revelation. And this one is not going to come as a surprise, you know, to someone like Dan, or really to any of the people here who are part of the Dan Friedman intellectual tradition, which I like to call the Dan-aspora – and of course that includes a lot of you.

And that revelation, of course, was that it was actually about interpreters the whole time! So, despite having been on this sort of long side quest into distributed computing all these years, it turned out that a lot of what my students and I had been doing all this time was still all about interpreters and interpretation.

So, you know – oops.

So in the rest of this talk, I’m going to discuss a couple of our group’s projects that exemplify this realization that I had. And both of these projects are about distributed systems, but I’m going to talk about them through the lens of interpreters. So of course this obligates us to try to answer this question of “What is an interpreter?”

So by the way, I would like this to be interactive if possible, so, you know, for those of you who are on Zoom, feel free to put peanut gallery comments in the chat. They won’t be a distraction to me; in fact, I enjoy it. So I’m interested in people’s takes on, you know, what exactly is an interpreter.

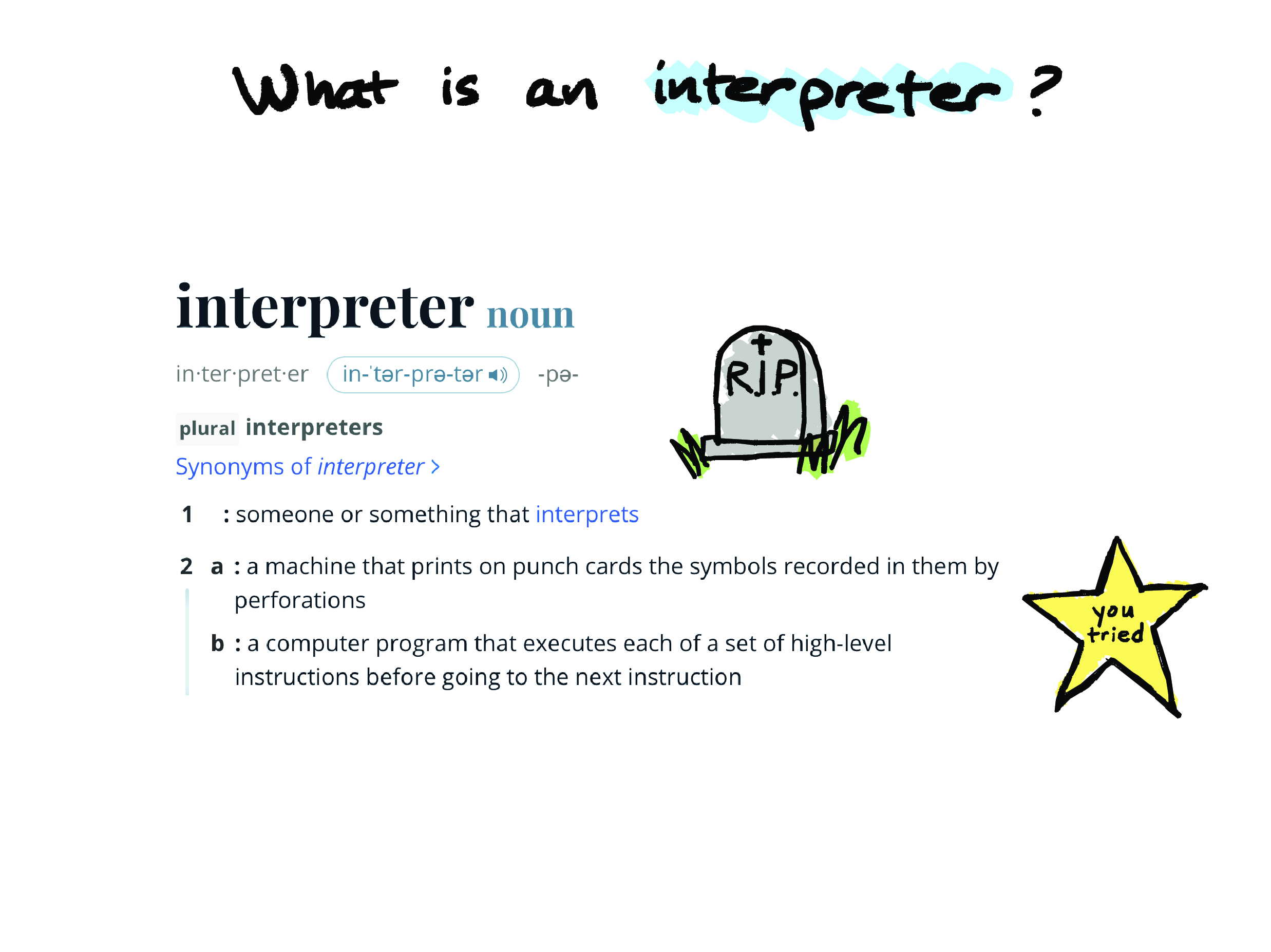

So, what exactly is an interpreter? Well, first let’s see what the dictionary says. And this is actually a shout out to Ken Shan, who, when I asked on Mastodon what an interpreter is, he helpfully sent me this dictionary definition, which is “someone or something that interprets”.

Well, okay, “thanks”. That’s not actually very helpful at all.

But there’s another definition that’s more computing-specific! Let’s see what that one says. There are actually two definitions here. One is “a machine that prints on punch cards the symbols recorded in them by perforations”. Hmm, okay. And the other is “a computer program that executes each of a set of high-level instructions before going to the next instruction”.

Okay, well, “you tried”. I think this definition is pretty bad also. I think we can do much better than this!

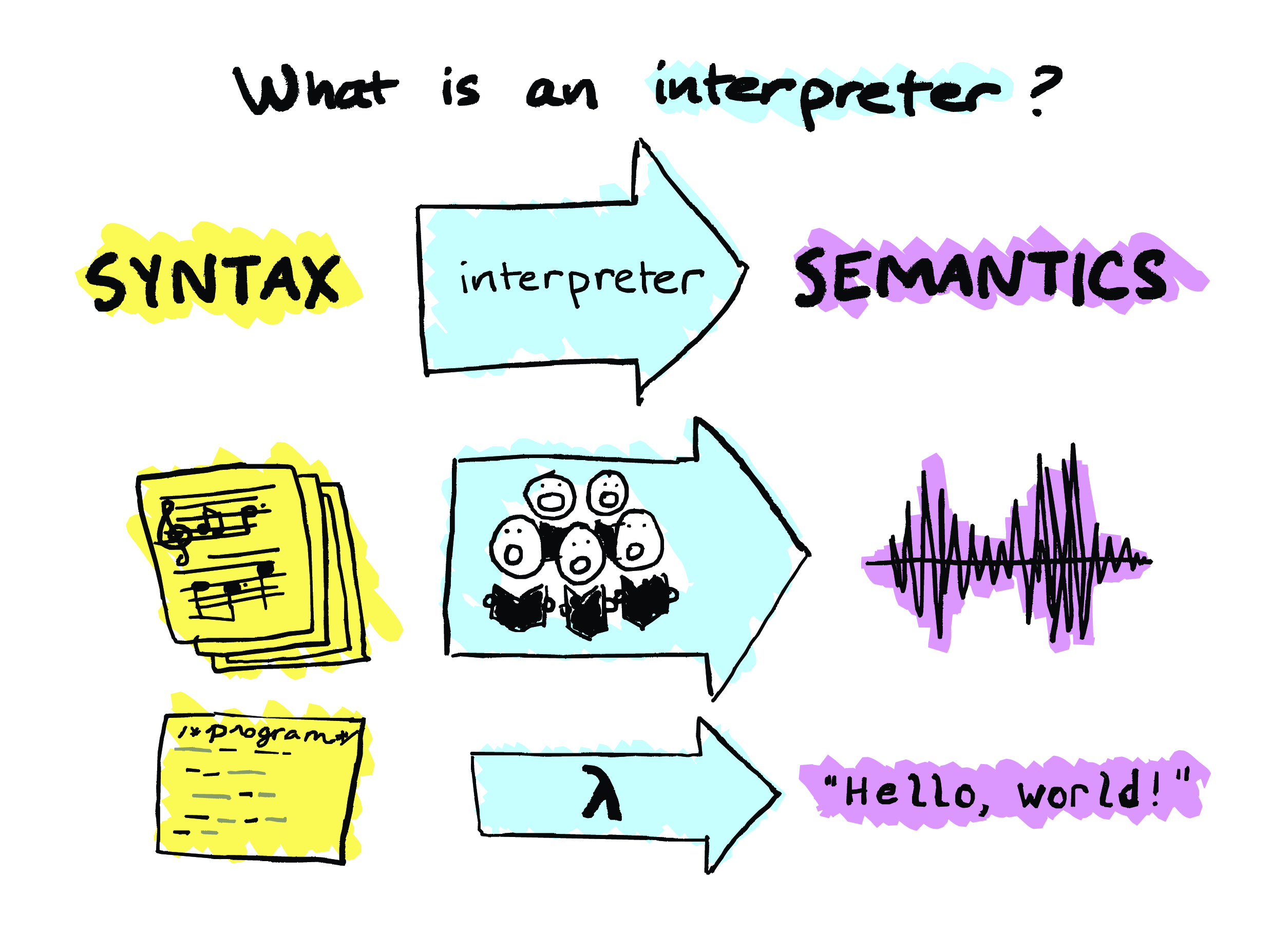

Okay, so how am I gonna define what an interpreter is? So, for the purposes of this talk I’m going to say that an interpreter is something that takes syntax and produces semantics.

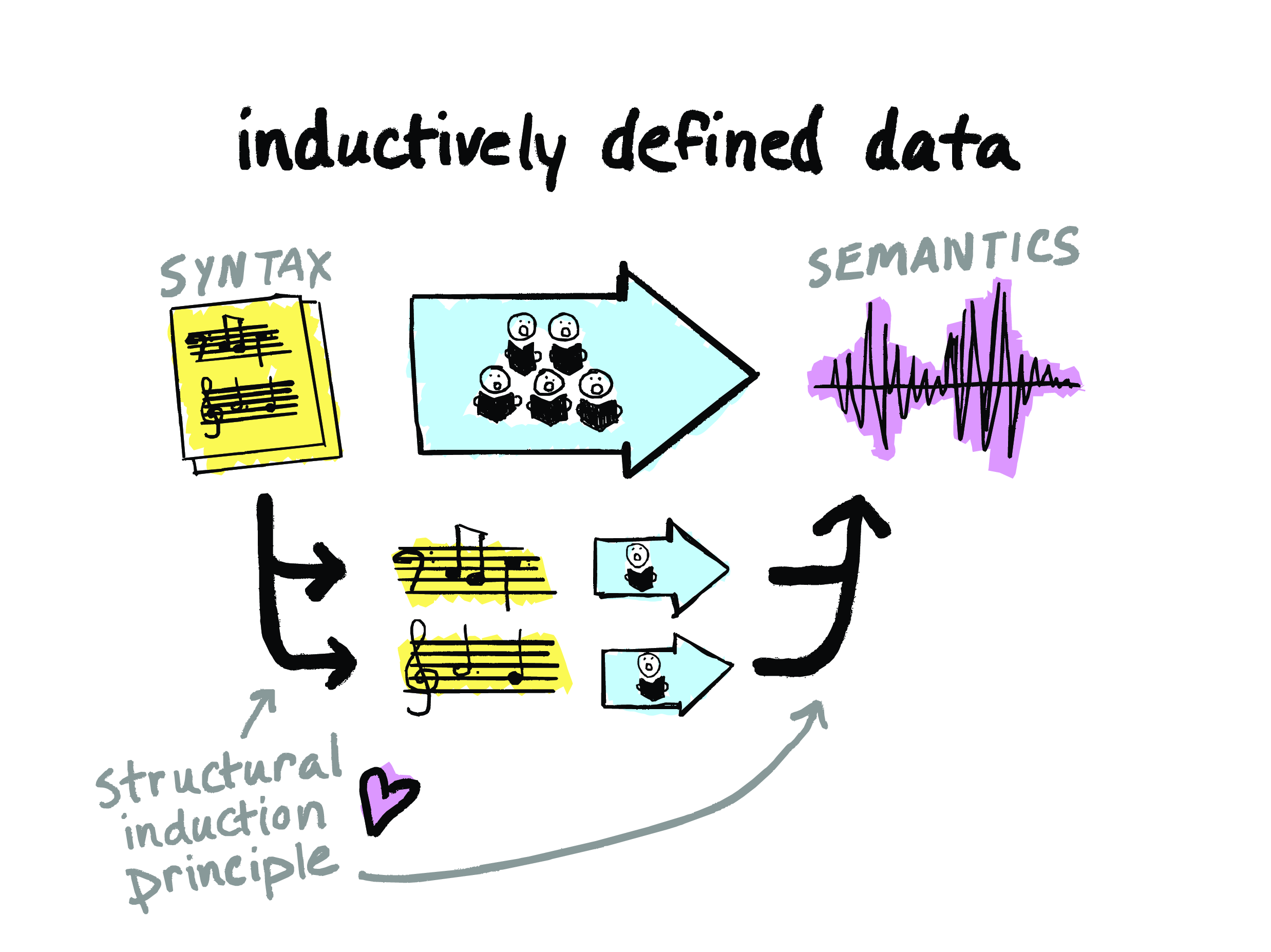

I like the generality of this definition. It lets us plug in domain-specific notions of “syntax” and “semantics” for whatever domain we care about. And it doesn’t even have to be computing-specific. For example – and this analogy is due to my friend CF – we can think of a choir as an interpreter. I’m a choral singer myself, and this analogy makes a lot of sense to me. It’s the choir’s job to interpret a musical score – usually aided by a director, who, you know, for the purpose of this analogy, we can think of the director as part of the choir – it’s their job to interpret the score and ultimately produce some audible music.

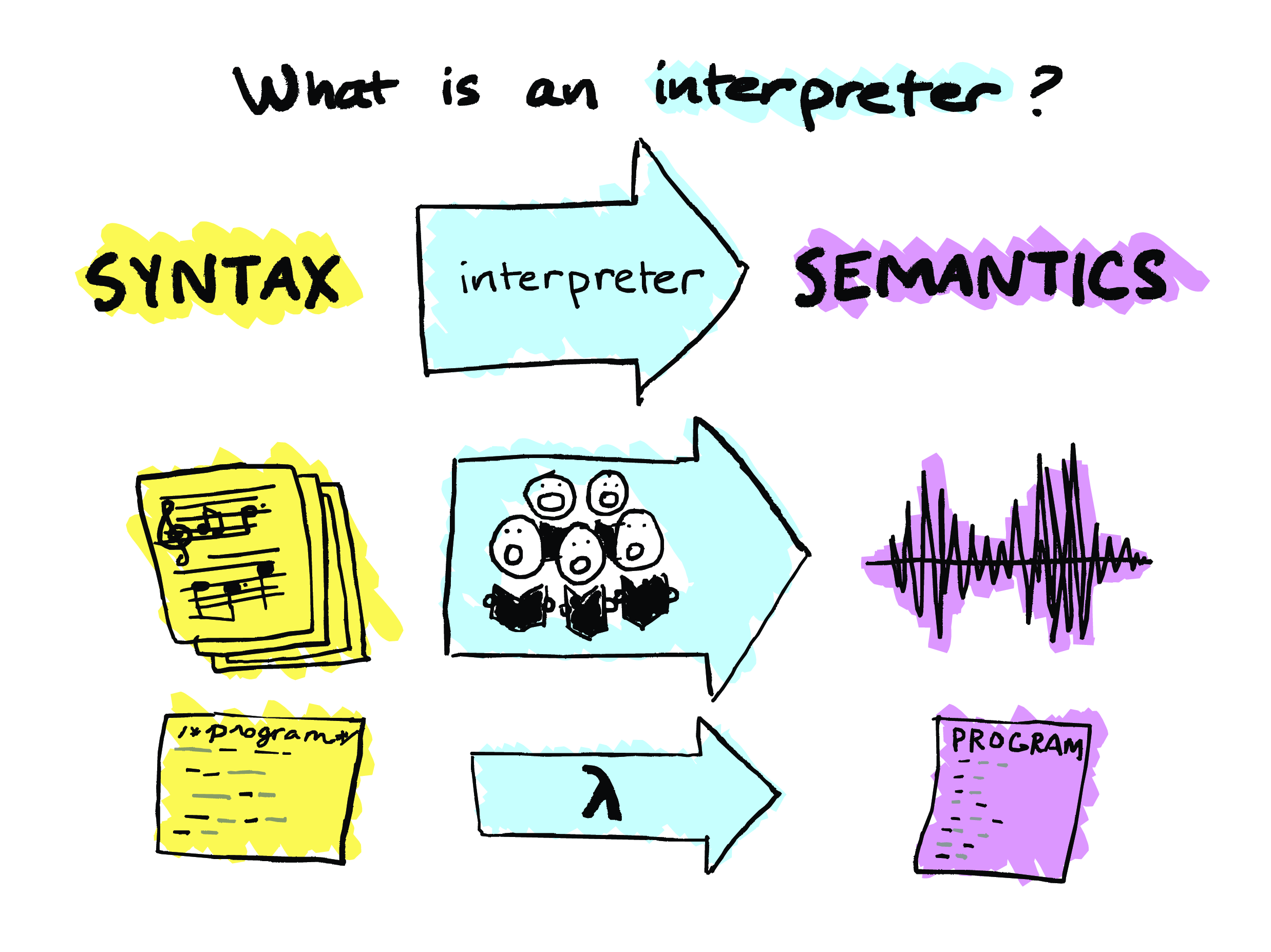

In computing, we might think of an interpreter as something that takes a program and produces a value. I’m using the word “value” here, but I’m using it pretty loosely, because that sounds very pure and like there aren’t any side effects, but a program might well have some sort of effect on the world. I’m not even going to attempt to define “program” here, except to say that both this notion of “program” and this notion of “value” might be domain-specific.

I’ll also point out that the value you produce here might even itself be a program! In which case, what is this last arrow on this slide? Well, now it’s actually a compiler, right? Because you’re taking a program and you’re producing a program. So, you know, at risk of annoying Jeremy and the other compiler folks here, I’m going to argue that, for the purposes of this talk, a compiler can be thought of as just a special case of an interpreter. And I would also argue that every programming language is “interpreted”, because sooner or later your code will be executed by the CPU, and a CPU is itself an interpreter. So it’s interpreters all the way down.

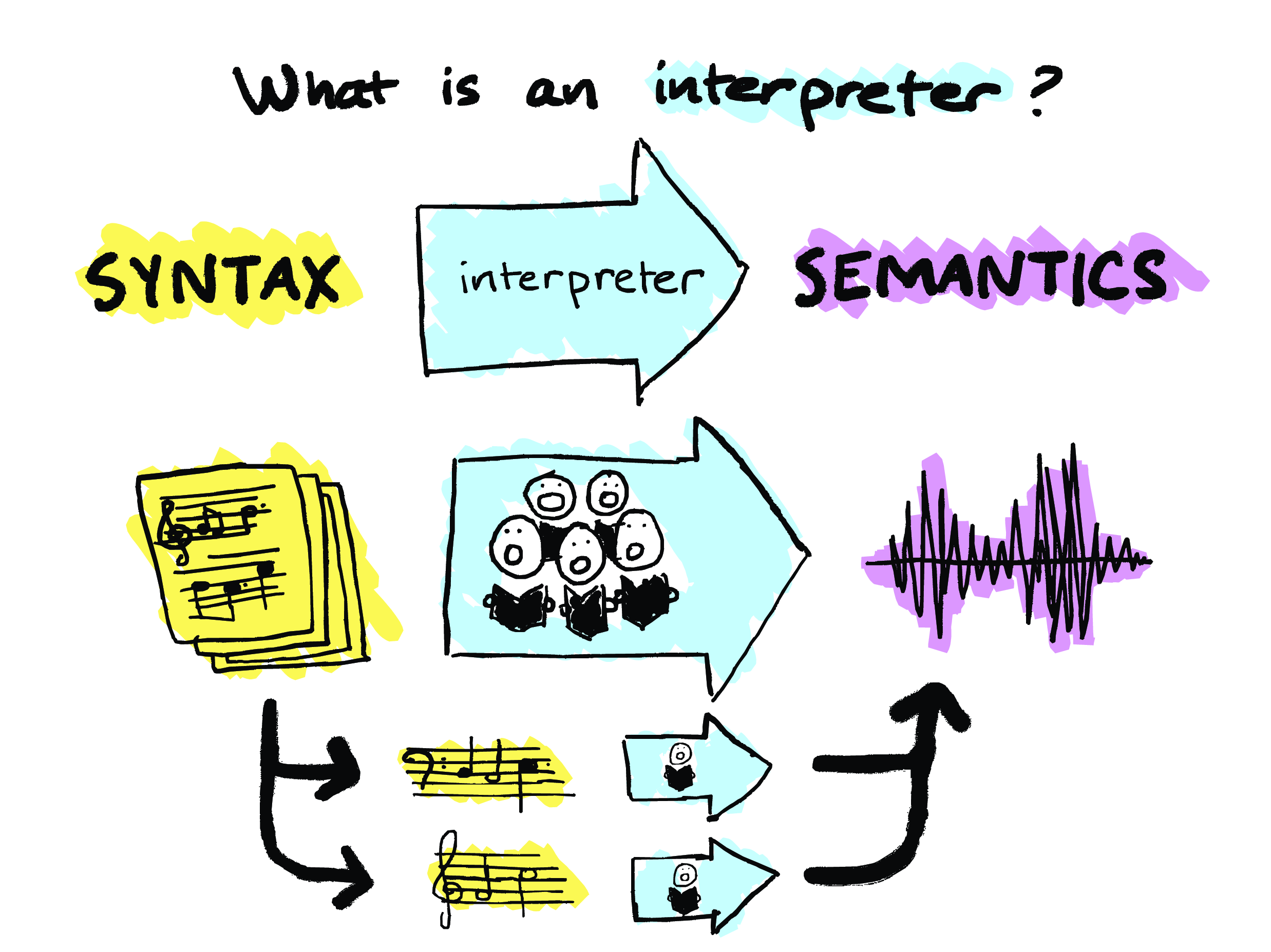

And there’s one last really important thing that I want to mention about what “interpretation” means. So – if you’ll continue to indulge me with this choir analogy – so, a music score for a choir is typically going to have different parts, right, that different people sing. So, if we say that syntax is interpretable, then that usually is going to connote something about the form that that syntax takes. In particular, it’ll say something about how the interpretation of a given input has to be determined by the interpretations of its subcomponents, and the result you get is compositional. To be able to do this, there has to be an obvious way to break down the input into its subcomponents and put them back together. In other words, it has to be inductively structured data – you know, like an AST.

So what I want to do next is dig into a couple of specific places where this idea of interpretation seems to have arisen in my own work in these last several years.

I’m going to focus on two projects from that list that I gave earlier, and those are library-level choreographic programming and causal separation diagrams. I’m going to talk about both of these things, and I won’t really have time to do more than just scratch the surface of either of them, but I’m really happy to dig into the details in Q&A, or chat with folks later. So, let’s jump in, and let’s talk about library-level choreographic programming first.

Library-level choreographic programming

Okay, so let’s talk distributed systems!

In the world of distributed computing, we’re usually concerned with message passing. The idea here is that you have some independent nodes that communicate with each other via a network, and they do it by sending and receiving some kind of messages. They don’t share memory, so the only way for them to coordinate with each other is by passing messages. And you might be able to imagine having some sort of so-called “distributed shared memory” as an abstraction on top of this, but under the hood, it’s ultimately all message passing.

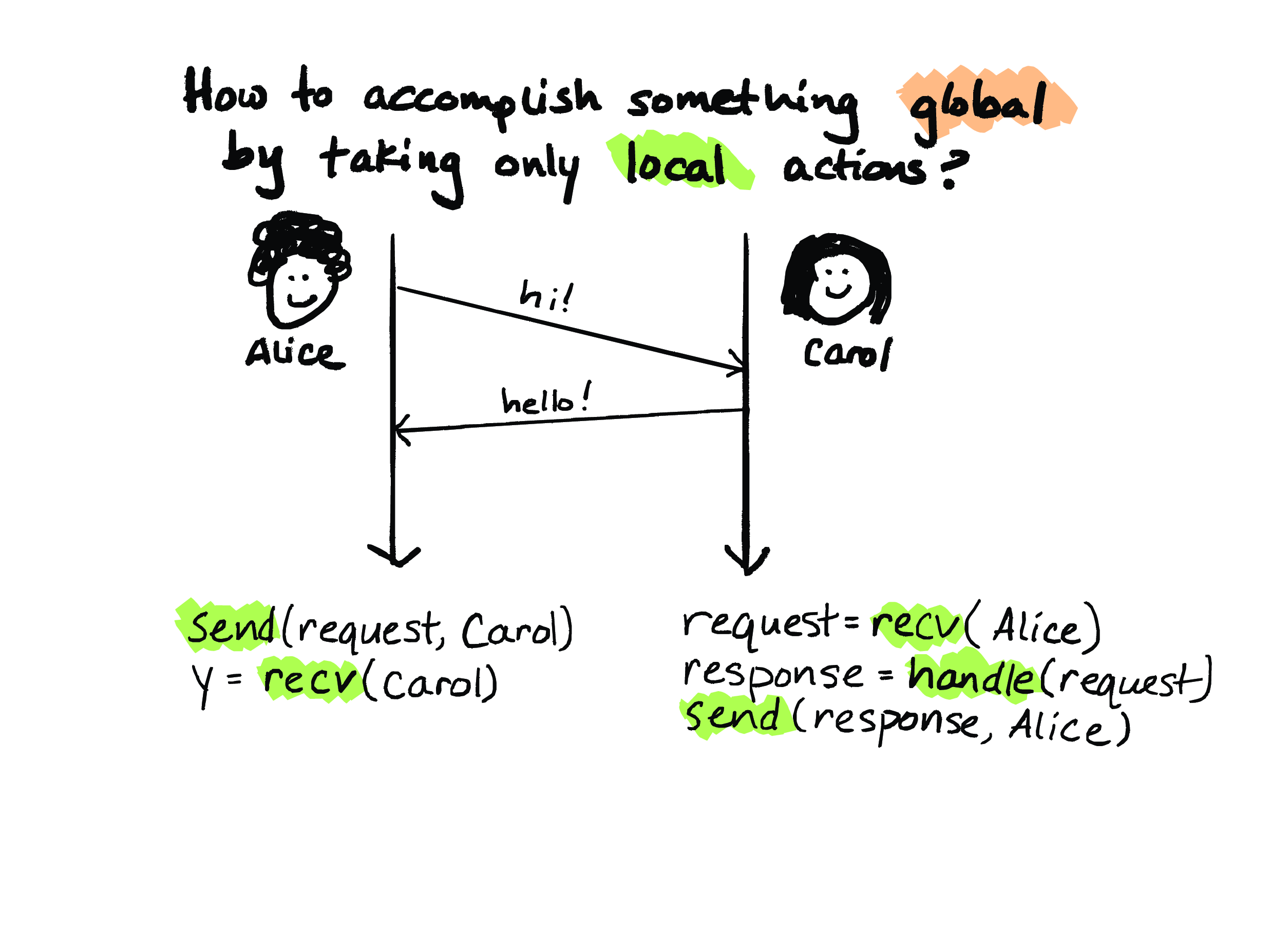

So, let’s suppose that our independent nodes are Alice and Carol. And there’s typically some kind of, you know, global behavior that we want here. And Alice and Carol have to together accomplish that, but they have to do it by taking only local actions, so the only thing that either of them can do is send messages, or receive messages, or take internal actions.

So, if we want to run a really, really simple protocol in which Alice sends a request to Carol and Carol responds to Alice, how do we program that?

Well, we can assume for now that we have some sort of send and recv functions that actually implement the message transport somehow, so it might be TCP, it might be HTTP, it might be pigeons flying around. Let’s not worry about the details of how the transport layer is implemented; let’s just think about what Alice and Carol have to do assuming it exists.

So, for this protocol, Alice would run this node-local program here on the left, and it might look like this: send a request to Carol, and then wait to receive a response from Carol, which gets stored in this variable here.

Meanwhile, Carol is running her own node-local program, which might look like: receive request from Alice and store it in this variable request, then do something to handle the request, and finally send a response.

So this is just about the simplest distributed program that I could could conceive of, but even in this really simple program, notice how Alice and Carol are utterly dependent on each other to faithfully follow the protocol. So, for instance, if Carol neglected to call recv over here, now that’s become Alice’s problem. So Alice will wait forever to get a response, or what she might do is time out and report an error, depending on how send is implemented. So in general, in a distributed system, nodes have to execute messages in this very careful dance where a message sent from a node has to be expected by some recipient, and vice versa. So if somebody is running buggy code, then things go wrong for somebody else.

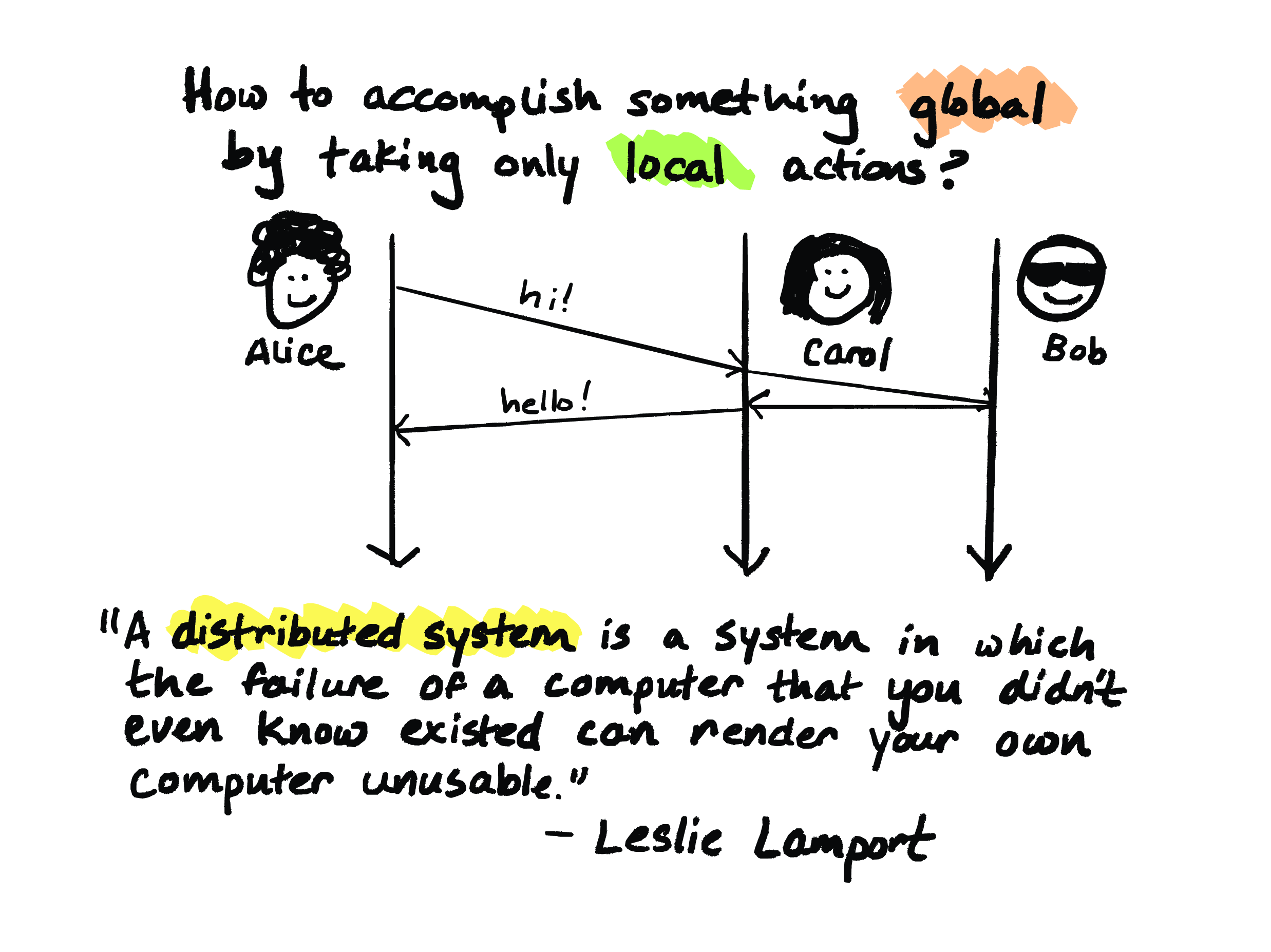

And it only gets more complicated if we add nodes. Let’s say that Alice is sending Carol a request, and then Carol is supposed to pass the request along to Bob, and then get an acknowledgment from Bob, and finally respond to Alice to acknowledge her request. This is the sort of pattern that you might see, for instance, in primary-backup replication, where – let’s say Alice is the client, Carol is the primary, and Carol gets a request from Alice which she has to pass on to Bob, Bob has to ack Carol, and Carol has to ack the client. In this scenario, Alice may not even know that Bob exists. But nevertheless, if Bob is misprogrammed, then that could mean bad news for Alice.

In fact this, example calls to mind this wonderful quote from Leslie Lamport in which he defines a distributed system as “a system in which the failure of a computer that you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable.”

So the challenge, then, for programmers is to try to reason about the behavior of this distributed system – the implicit global behavior of this system – while writing the explicit local programs – which are just sends and receives and internal actions – that actually run on the nodes.

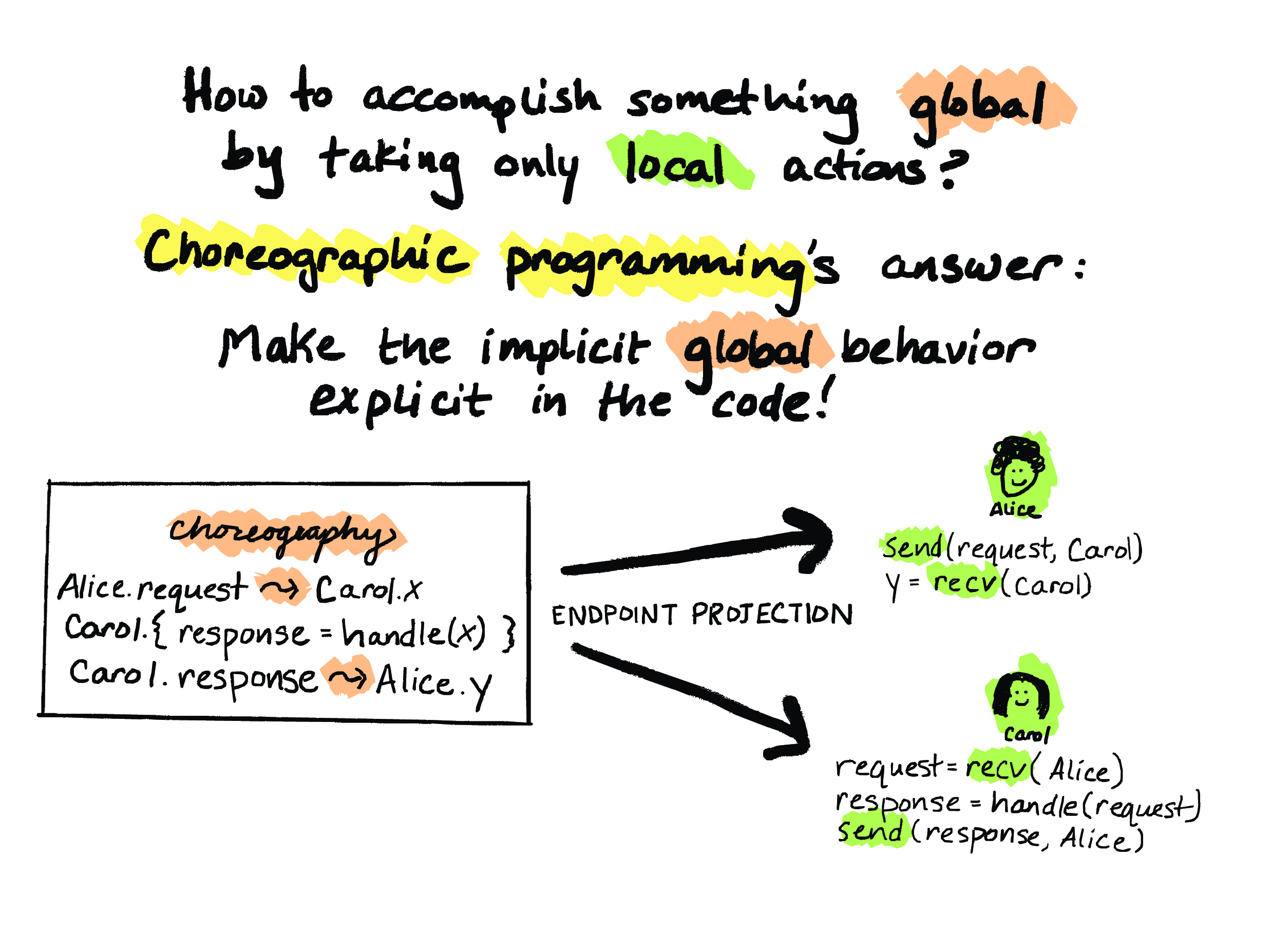

So, this brings us to choreographic programming. And the idea of choreographic programming is: let’s make that implicit global behavior actually explicit in the code! In choreographic programming, we don’t write the local programs at all. Instead, we write a single, global program that’s called a choreography. And then we generate a collection of local programs, one for every node, from the choreography, via a technique called endpoint projection.

So what we have on the left here is a choreography that expresses the protocol that we talked about earlier. So, every choreographic programming language is going to have some sort of operator like this highlighted squiggle-arrow ~> here. And this is usually pronounced “comm”, because it denotes communication between two parties.

So, looking at this first line here in the choreography, a ~> expression is going to express a both send and a receive at once. And what this means is that Alice is going to compute this value request, communicates it to Carol, Carol receives it and stores it on her end in the variable x. When this choreographic program gets projected, every time you have an occurrence of Alice on the left-hand side of a ~>, it’s going to turn into a send call on Alice’s node, and every time you have an occurrence of Carol on the right-hand side, that’s going to turn into a recv on Carol’s node.

Thanks to this way of writing code, as long as our endpoint projection is correct, we can rule out the possibility of a mismatched send and receive, and we can therefore rule out a certain kind of bugs that could occur in our collection of local programs that we end up with. In a nutshell, that’s the benefit of choreographic programming.

I do want to acknowledge one of the elephants in the room, which is that with what we’ve shown so far, choreographic programming per se doesn’t actually do anything to help us if one of these nodes should crash, or if one of these messages should be lost. So, those fault tolerance problems were present in the non-choreographic version of the code, and they’re still present here. So choreographic programming doesn’t do anything to fix that as such.

What it does do is rule out programming errors that stem from a programmer not calling send where they should or not calling recv where they should. In a simple program like this, that might not seem like such a big deal. But once more parties are involved, it becomes less simple, and it’s in that multi-party setting where choreographies really shine. So next let’s look at a setting with three participants and with some more interesting control flow.

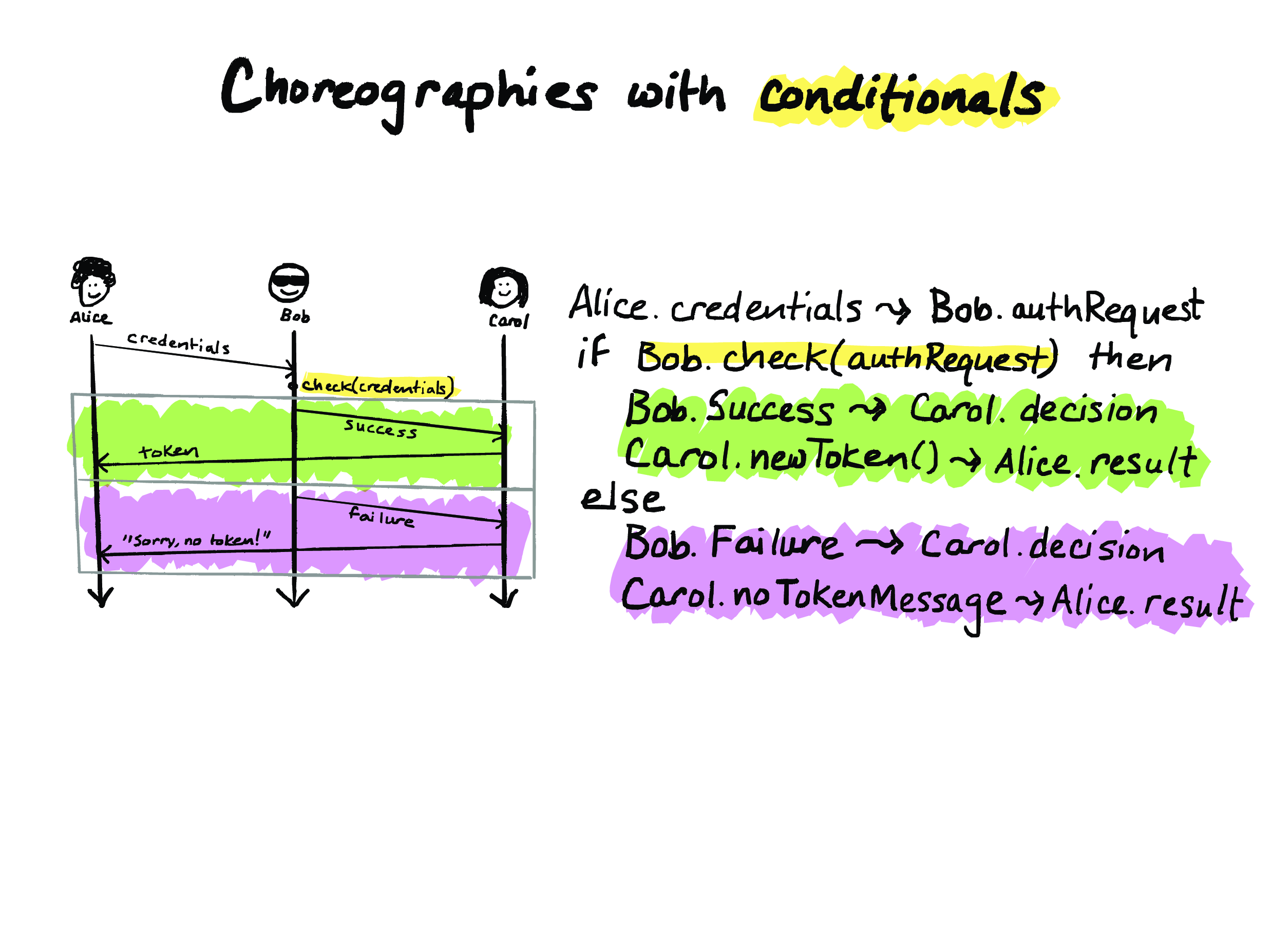

OK, so this is a slightly more interesting protocol. Suppose that Alice wants to interact with Carol, but Bob stops her to check her credentials first. So, this example is kind of like a sign-on through an third-party authentication service.

And by the way, this example is straight from the choreographic programming zine that my student Ali and I wrote last year, which you can get from my website if you want. In the zine it’s that Alice wants to go to Carol’s birthday party but she’s stopped by the bouncer Bob.

In this protocol, Alice has to have her credentials verified by Bob before she can interact with Carol. So, Alice sends those credentials to Bob. Bob runs this check function on Alice’s communicated credentials, and then, depending on the outcome of that, Alice will either get an access token from Carol or not. So this diagram represents two different ways that an execution might go.

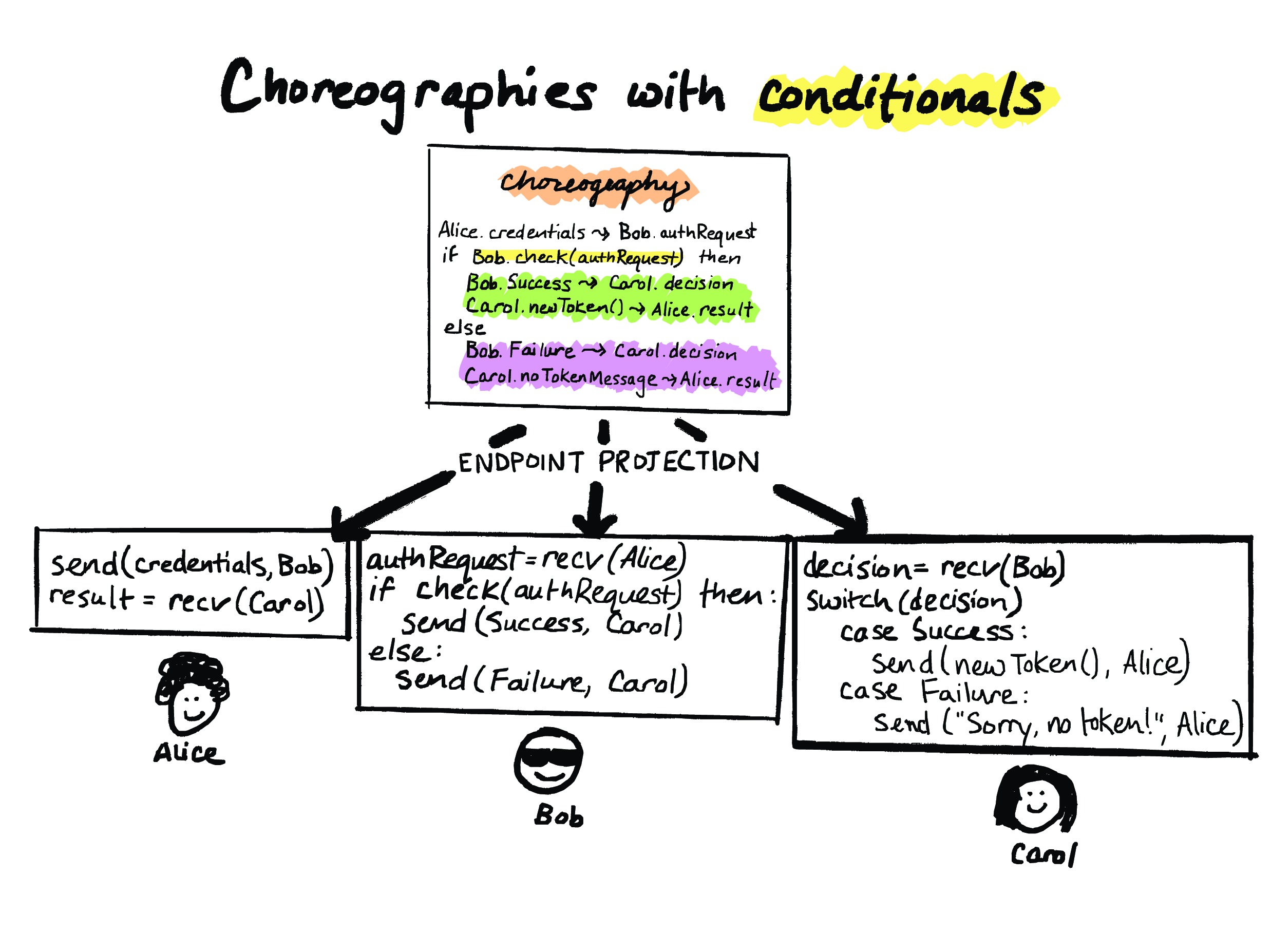

So, how do we express this in a choreography? Well, in a choreography, we can have conditionals at the choreography level, and here’s what that looks like. So, on the first line, here’s our squiggle-arrow again. And this notation Alice.credentials ~> Bob.authRequest means Alice is computing something called “credentials” and then sending it to Bob, who receives it and then stores it on his end in this variable called “authRequest”.

And then we have a conditional. So, the conditional check takes place locally on Bob’s node. And then, depending on which branch we take, either Bob communicates “Success” to Carol, who then communicates the token to Alice, or Bob communicates “Failure” to Carol, and then Carol tells Alice that she can’t have the token.

So what I think is useful to point out about this execution is that even though the execution is spread out across these three different parties – so this is a distributed execution – if we think about the execution globally, this is actually a sequential program in which steps happen one after the other. And we can see that from reading the choreography; the choreography just looks like straight-line code. In fact, the choreography looks remarkably similar to our informal diagram that we drew. So, if we were to write this code as a traditional distributed program, which is really three programs running on the three participants, then the control flow wouldn’t be as obvious. So having it as a choreography actually helps the readability of the code as well.

OK, so to actually run this thing, we need to do endpoint projection on it. So, endpoint projection will take this choreography and it’ll project it to versions running on Alice, Bob, and Carol, and this is done automatically by the choreographic language implementation. And I’ve written some pseudocode to give an idea of what the projected code might look like. And notice, like I said, in this projected code, the control flow isn’t as clear. You might have to stare at it for a bit to figure out what’s supposed to happen first, what’s supposed to happen second. So choreographies give us this readability advantage.

There’s some stuff that I’m leaving out here. One important side note here is that when you do endpoint projection, if the choreography had a conditional like this, then the parties that are involved need to be told what branch to take. And this is called the “knowledge-of-choice” problem. Different choreographic languages have different ways of dealing with this. For instance, if I hadn’t had code in my projected code that commmunicates the outcome – or if I didn’t have code in my choreography, rather, that communicates the outcome of this check(authRequest) call, then some choreographic languages would then complain that the choreography is what we call “unprojectable”. And other languages would just insert the necessary communication code for you. So that’s all an interesting problem in its own right, and if you’re interested in knowing more about that, then I’m happy to talk more about it later.

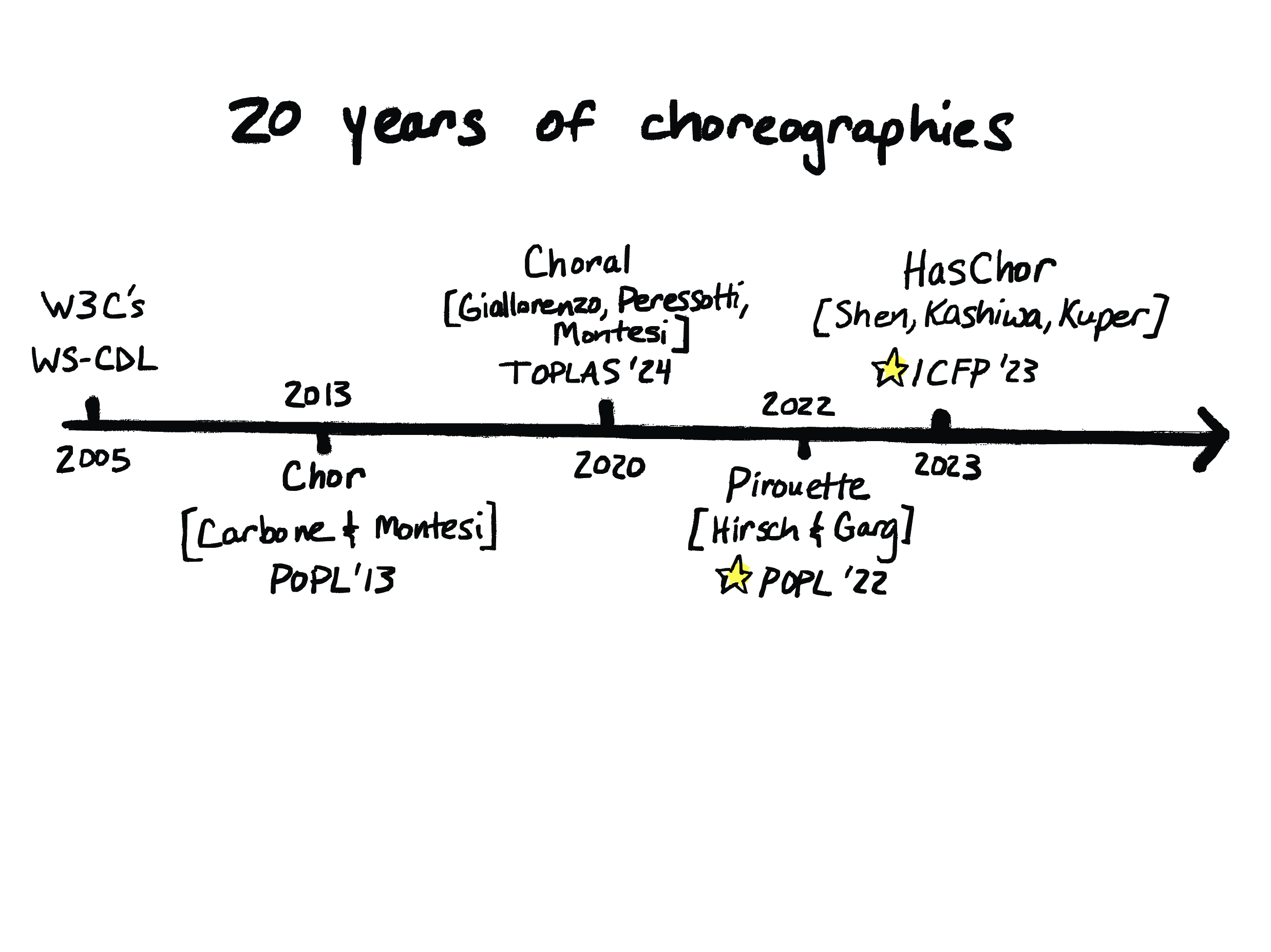

OK, so now you know what choreographic programming is. So, we didn’t invent any of this stuff; choreographies have been around for a long time. Dating back to the early 2000s, there was something called the World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Services Choreography Working Group, and they developed a draft specification for a language called WS-CDL, which stood for Web Services Choreography Description Language. However, this wasn’t intended to be executable; it was only a specification language – you couldn’t actually run these things.

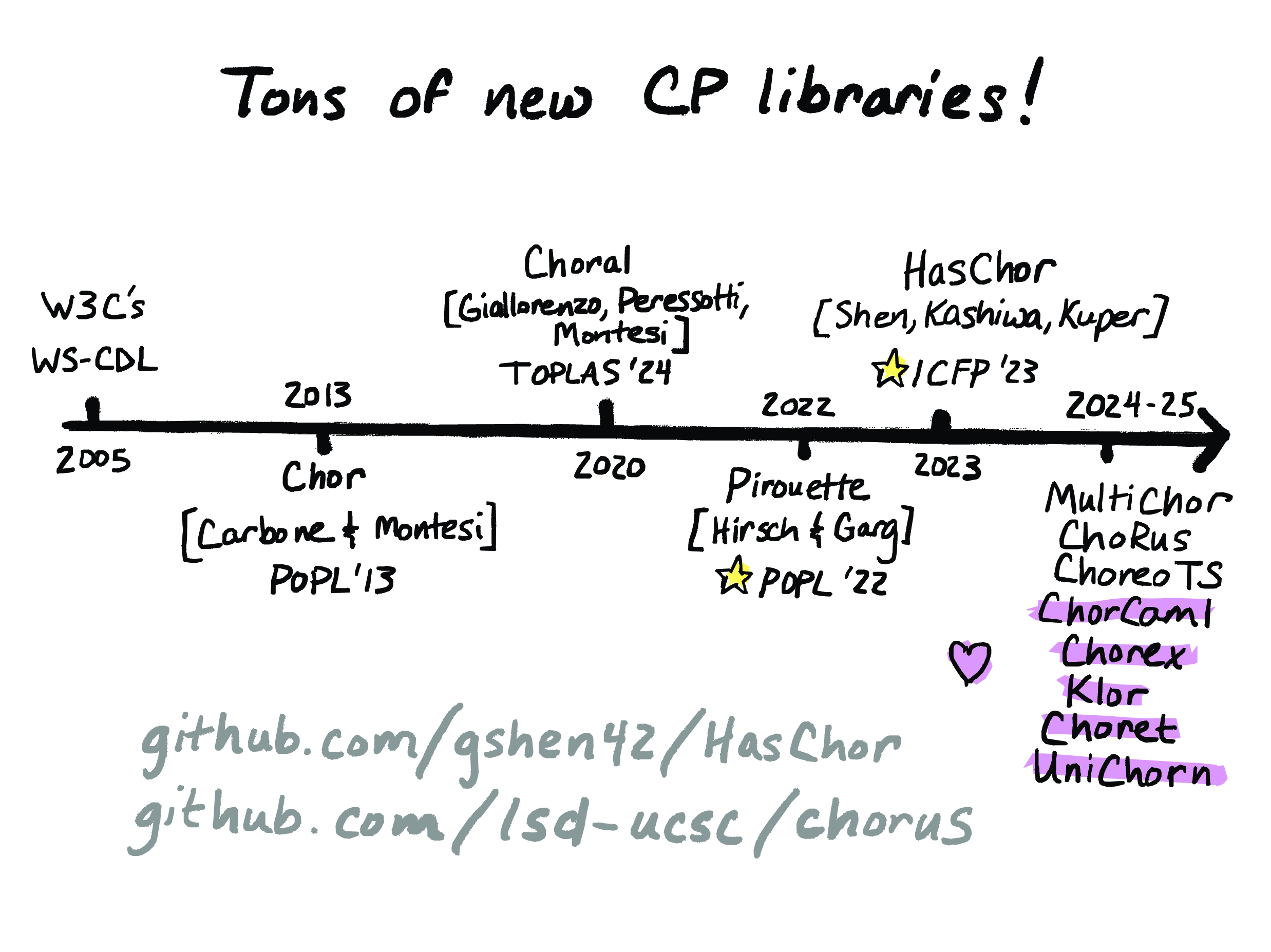

So, fast forward to 2013, when there was a language called Chor developed by Marco Carbone and Fabrizio Montesi. And this pioneered the idea of an executable choreographic programming language that used endpoint projection to compile choreographies to these runnable node-local programs.

Then in 2020, Fabrizio Montesi teamed up with Saverio Giallorenzo and Marco Peresotti to create the Choral programming language. And Choral is intended to be useful for realistic programming, and it’s notable for how it uses mainstream object-oriented programming abstractions, so it’s designed to be familiar to, say, Java programmers. And the Choral compiler projects choreographies to executable Java code.

Then, in 2022, Andrew Hirsch and Deepak Garg created a choreographic language called Pirouette, which combined choreographic programming with higher-order functional programming. This paper made a splash in the functional programming research community, and it won a Distinguished Paper Award at POPL that year, and this is how my students and I found out about choreographic programming for the first time. And this paper, by the way, is also notable for its mechanized proof of deadlock freedom.

So, my student Gan Shen read the Pirouette paper and decided he wanted to try implementing a choregraphic language himself. And so, being who he is, the approach that seemed obvious to him was to do it as an embedded domain-specific language in the form of a Haskell library. And the idea is really straightforward, and what’s funny about this is that Gan wasn’t even trying to do something novel – he just wanted to learn about choreographies. But it turned out, to our surprise, that this idea of implementing a choreographic language purely as a library had not been done before. And this appeared at ICFP ‘23, where it also won a Distinguished Paper Award. (So for a couple years in there, every paper about choreographic programming in PACMPL was getting a Distinguished Paper Award – sadly, no longer true.)

So let’s dig in a little bit and talk about HasChor and how it works.

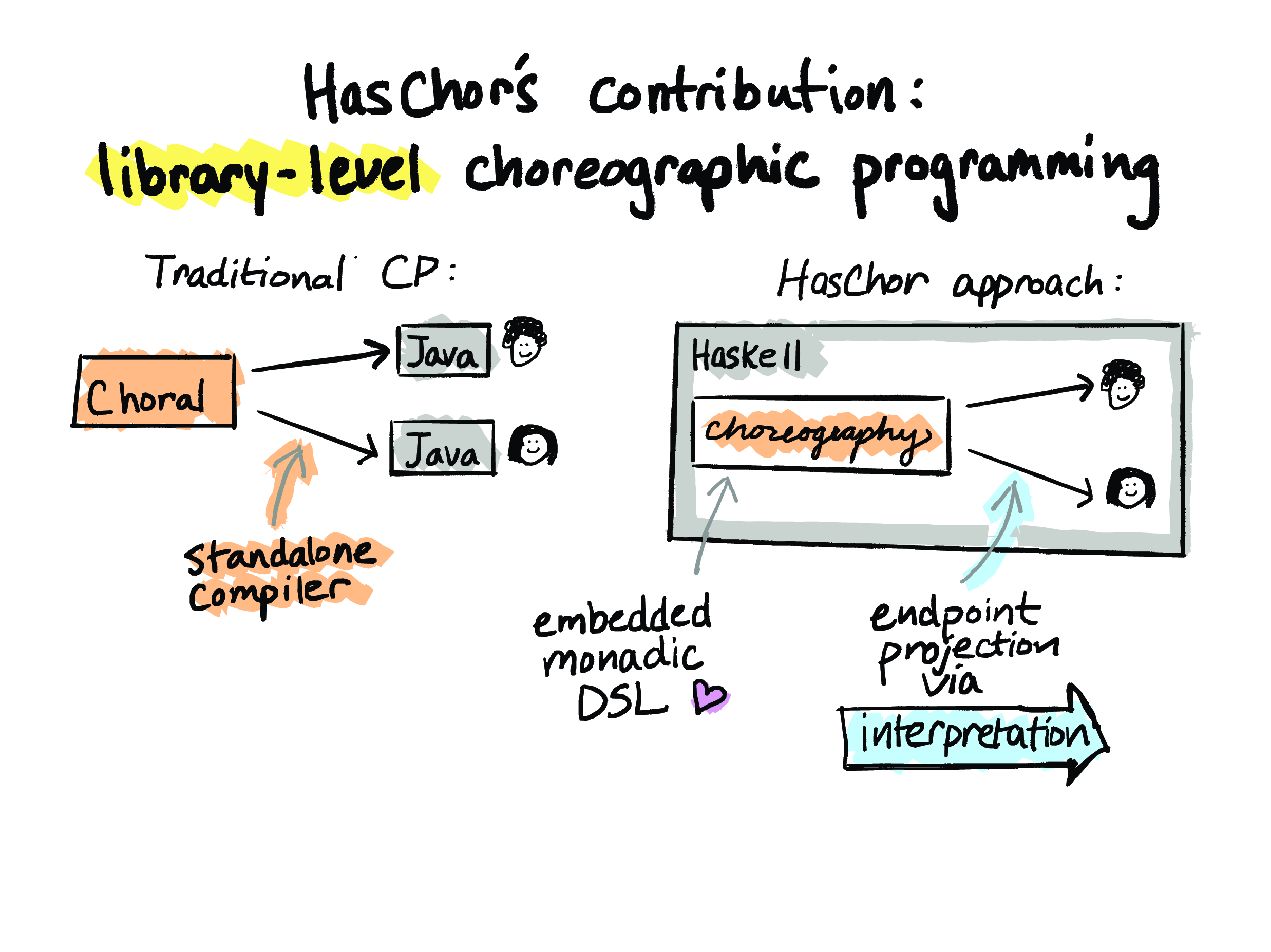

So I’m gonna contrast this with the traditional approach to choreographic programming, which is exemplified here by Choral. In Choral, you write a choreography in the standalone Choral language and you compile it to executable endpoint code using a standalone compiler. So Choral compiles to Java, and then you can run those Java programs using the usual Java toolchain. And this all works fine, but it means that you need this purpose-built language and this purpose-built compiler.

In HasChor, on the other hand – and this is our framework – choreographies are expressed as programs in an existing host language – in this case it’s Haskell – and the choreographic language constructs and endpoint projection are all implemented entirely in this host-language library, so there’s no additional compiler support needed, no additional runtime support needed beyond what the host language can already do.

So in particular, our choreographic language is implemented in Haskell as a DSL using something called a freer monad, which separates the interface and implementation of effectful computations. So by itself, this language doesn’t assign any meaning to choreographic operators like that ~> that I was talking about before. Instead, it just accumulates them as this big term, and then we dynamically interpret that term, based on the location where the code’s being run. So, for instance, that ~> operator: if you’re a sender, that gets interpreted as send, if you’re a recipient, it gets interpreted as recv, and if you’re anyone else, then it’s a no-op.

All the usual benefits of embedded DSLs apply here. So, because these programs in HasChor are really just Haskell programs, that means that a HasChor programmer can take advantage of the whole Haskell ecosystem. They can use their existing Haskell tools for development and debugging, they can use other Haskell libraries, and they can compile it just like any other Haskell program. Whereas, for something like Choral, it’s a whole new language, right? You might not have any tooling unless the developers bother to implement it.

And there’s one other plus side, I think, to this embedded DSL approach, which is that it makes it easier to integrate choreographies into bigger non-choreographic systems, so there’s no need to change languages just to implement certain pieces as choreographies. And I think this is really important, because while choreographic programming may be a good fit for certain components of a program, there might be other parts of the program where trying to fit it into that choreographic paradigm just doesn’t make sense. So maybe you have a program where almost all of the code happens locally, but maybe there’s like a short-lived network interaction, just to do authentication or something. So then, you know, it wouldn’t really make sense to have to write everything in a choreographic language just so you could get the benefit of choreographies for that one little piece. So that’s an argument in favor of this library-level approach.

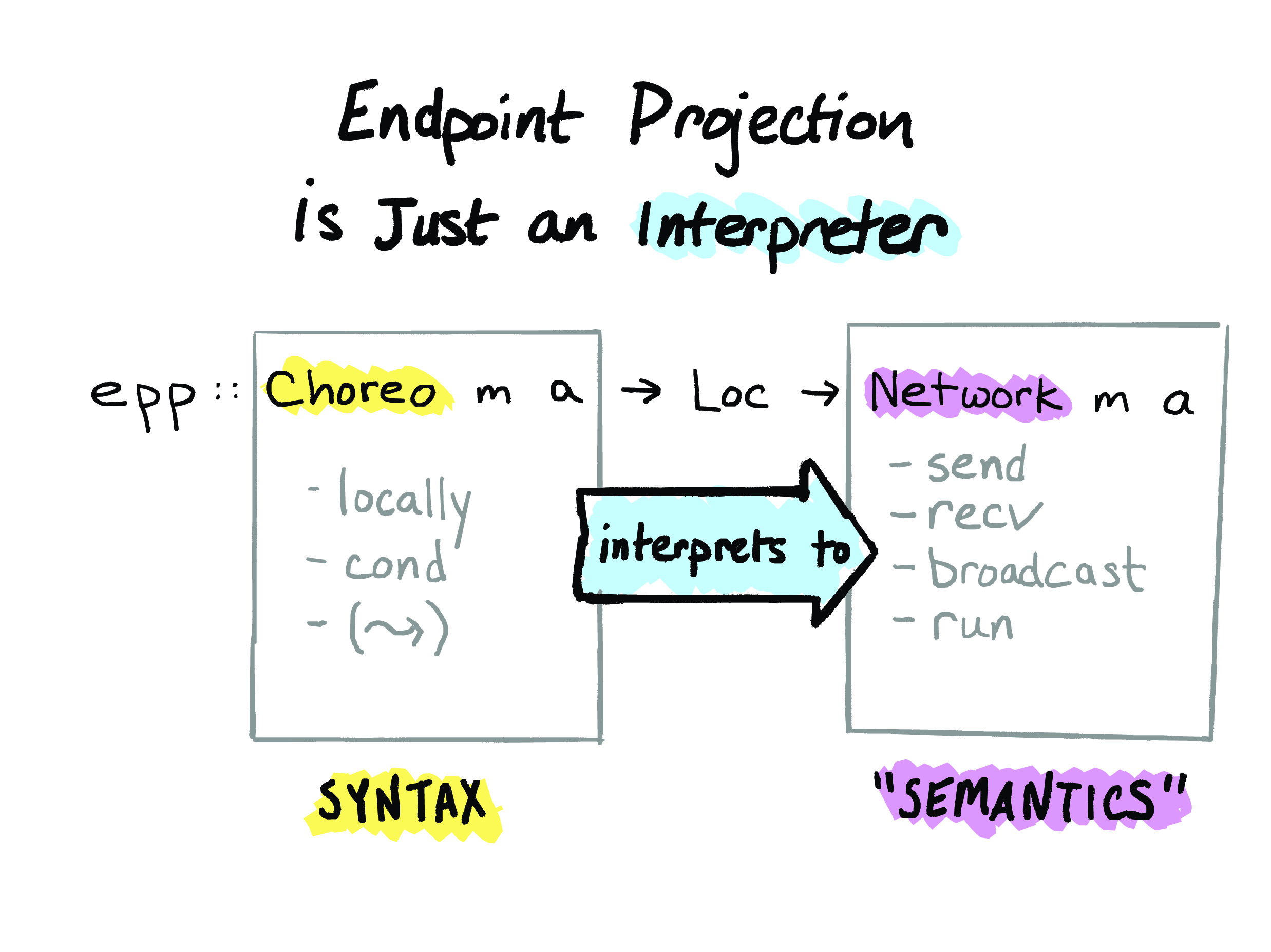

And one of the consequences of this is that endpoint projection actually happens dynamically, at run time. So let’s take a look at the type of the endpoint projection function in HasChor, and I hope to convince you that it’s really just an interpreter. I promise you that this is the only line of Haskell code that I’ll make you look at in this whole talk.

So, endpoint projection is a function that takes two arguments. The first argument is this Choreo thingie here, which is a choreography. So, endpoint projection takes one of these choreographies, and the second argument it takes is a location, which is the place we want to project the choreography to, so, like, Alice or Bob.

And endpoint projection returns something called a Network, which you can think of as a low-level program in terms of sends and recvs that’s been specialized to the location you gave as an argument.

So for the Haskell enthusiasts here, both Choreo and Network are freer monads. But you should think of them both as just being programs. And these choreographic operators that are in Choreo programs all get interpreted to things like send, recv, and broadcast in the Network programs. So Choreo gives us a syntax. On the Network side, we have – I’ve put “semantics” in quotes here, because this isn’t actually semantics, it’s still just syntax, and then that will get dynamically interpreted to the actual meaning of send and recv and so forth. The actual meaning of send and recv and so forth is going to be supplied by a network backend, and HasChor comes with two of those that you can choose between. There’s an HTTP backend which uses HTTP for the network transport, and there’s a local backend which implements these send and recv functions as communication among threads on a single machine. So that’s endpoint projection: it’s just an interpreter!

So, returning to our timeline of choreographic programming, it’s really exciting how since HasChor came out in 2023, a bunch more choreographic languages-as-libraries have popped up. So there’s a bunch more new choreographic programming libraries in these last two years. Some of them are from our group – so, MultiChor is a successor to HasChor, ChoRus is a choreographic programming library for Rust, ChoreoTS is a choreographic programming library for TypeScript – but what’s even more exciting to me is that a bunch of these are not from our group. So there’s ChorCaml for OCaml, there’s Chorex for Elixir, there’s Klor for Clojure, there Choret for Racket, and there’s UniChorn, which is for a distributed programming language called Unison. So all of these are doing dynamic endpoint projection, so endpoint projection at run time, just like HasChor, but they all do it using the idioms that make sense in those languages. So, for instance, Choret is built on top of Racket, and in Choret it’s done using macros, which is super cool. So all of these different approaches use the idioms that make sense in the languages that they’re implemented in, and I love that.

All right, and here I’ve just given the GitHub URLs for a couple of our projects. So here’s the HasChor repo and here’s the repo for ChoRus, which again, is our choreographic programming framework for Rust. So feel free to take a look at these and check them out. This is work led by my students Gan Shen and Shun Kashiwa, and then ChoRus was also – the lead author on it was Mako Bates, who is a recent PhD graduate from Joe Near’s group at the University of Vermont.

Okay! So, that’s it for the first line of work I wanted to talk about, on library-level choreographic programming.

Causal separation diagrams

And now I want to talk about causal separation diagrams. So, let’s talk diagrams!

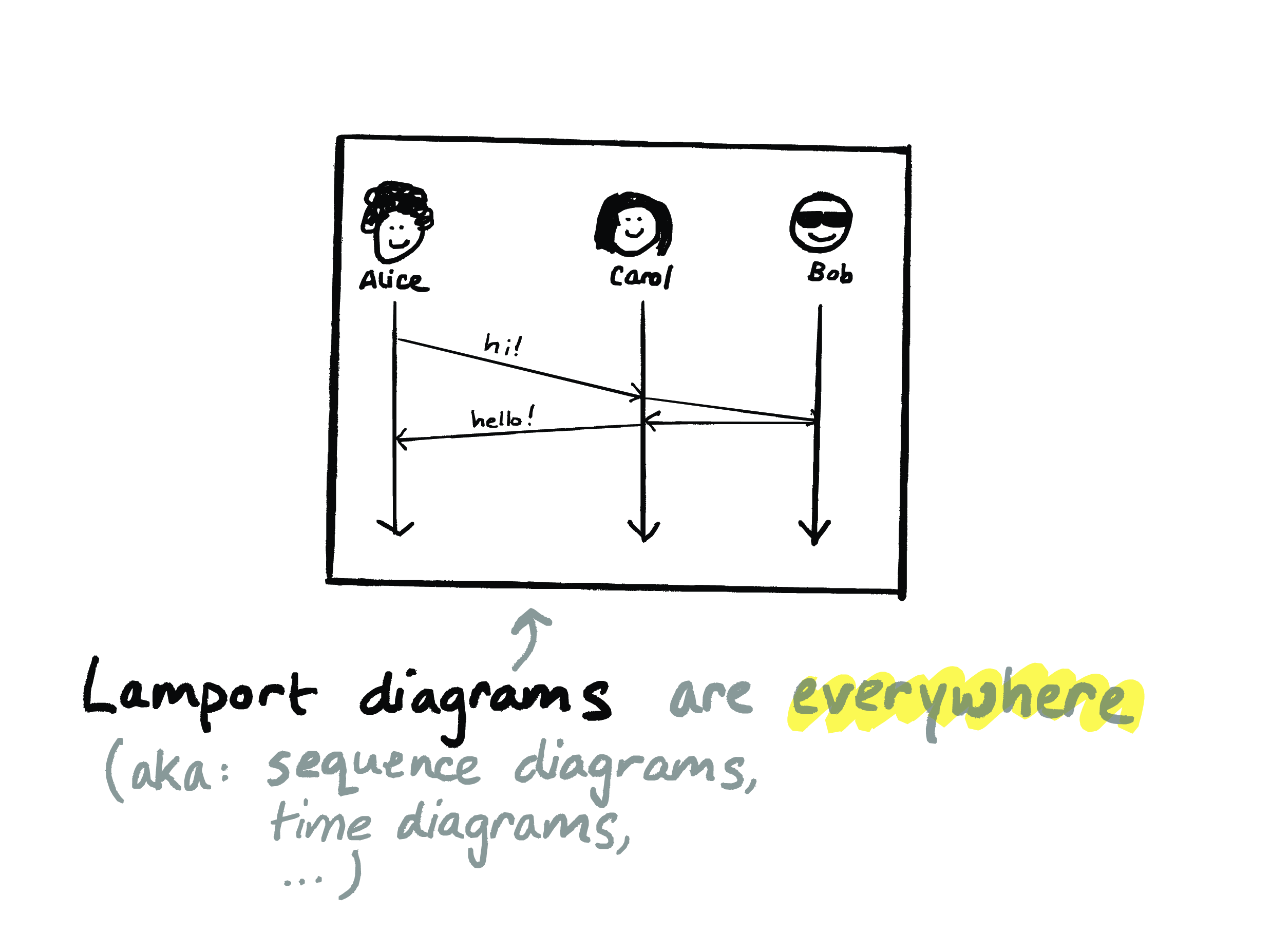

So, people who work on concurrent and distributed programming been using diagrams like these – I call them Lamport diagrams, but they’re also known as sequence diagrams and time diagrams and a bunch of other names – people have been using diagrams like these since – at least since the 1970s, as a way to try to wrap our heads around how concurrent and distributed systems work. I’ve been using them throughout this talk. And they’re pretty intuitive, you know? I didn’t have to explain what these diagrams mean. And you might have drawn one yourself on a whiteboard recently.

These diagrams depict the events of interest in a system – usually things like when message are sent or received – and the relationships between those events across space and time. And these diagrams are so intuitive that we see them at all levels of academia and industry.

But they are just pictures, right? They’re not formal objects – but they could be formal objects!

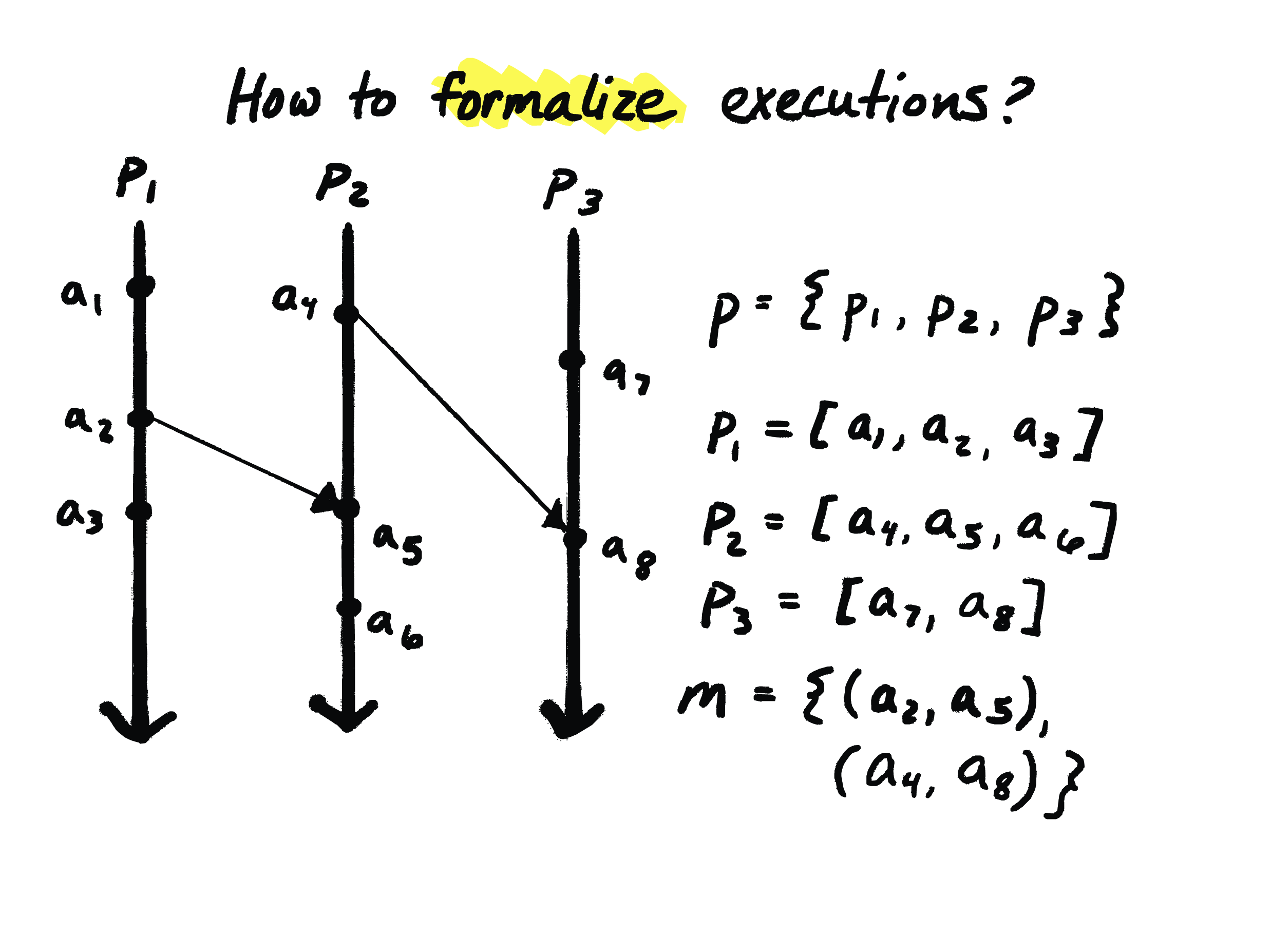

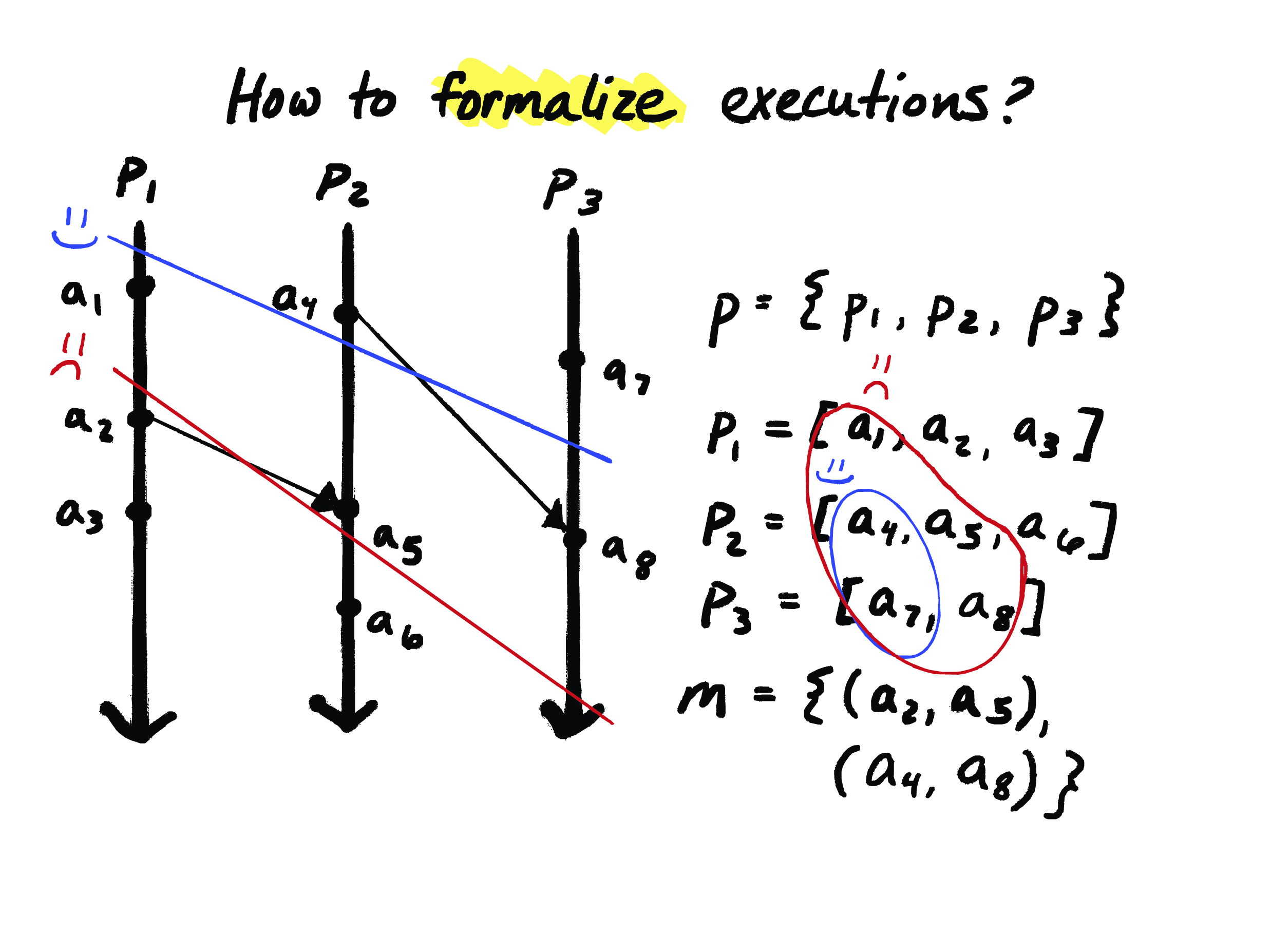

So, if we want to reason formally about executions like the one that’s shown here, we need a formal model of executions. So, let’s talk about how to do that. And I’ll put the diagram on the left here, and this textual formalism on the right, but these are really expressing the same information.

So the first thing we would need is a collection of processes, right? These are modeling whatever locations are participating in the system.

And then, every process is going to have a sequence consisting of the events that occurred on it. And events could be message sends, or they could be message receives, or they could be events that are internal to a process. So we have a sequence of events on each process that’s totally ordered.

And then, last, we’re going to have pairs of events that comprise “messages”, which is where information propagates from one place to another. So here, for instance, \(a_1\) would be a local event on this process \(P_1\), \(a_2\) would be a message send event, and the message is being sent to \(P_2\), where the receive event is \(a_5\).

So what I’m showing here is a completely standard way to formalize executions, and it get used all the time, with good reason. But it does have some pitfalls. So, what are some of the problems with doing it this way?

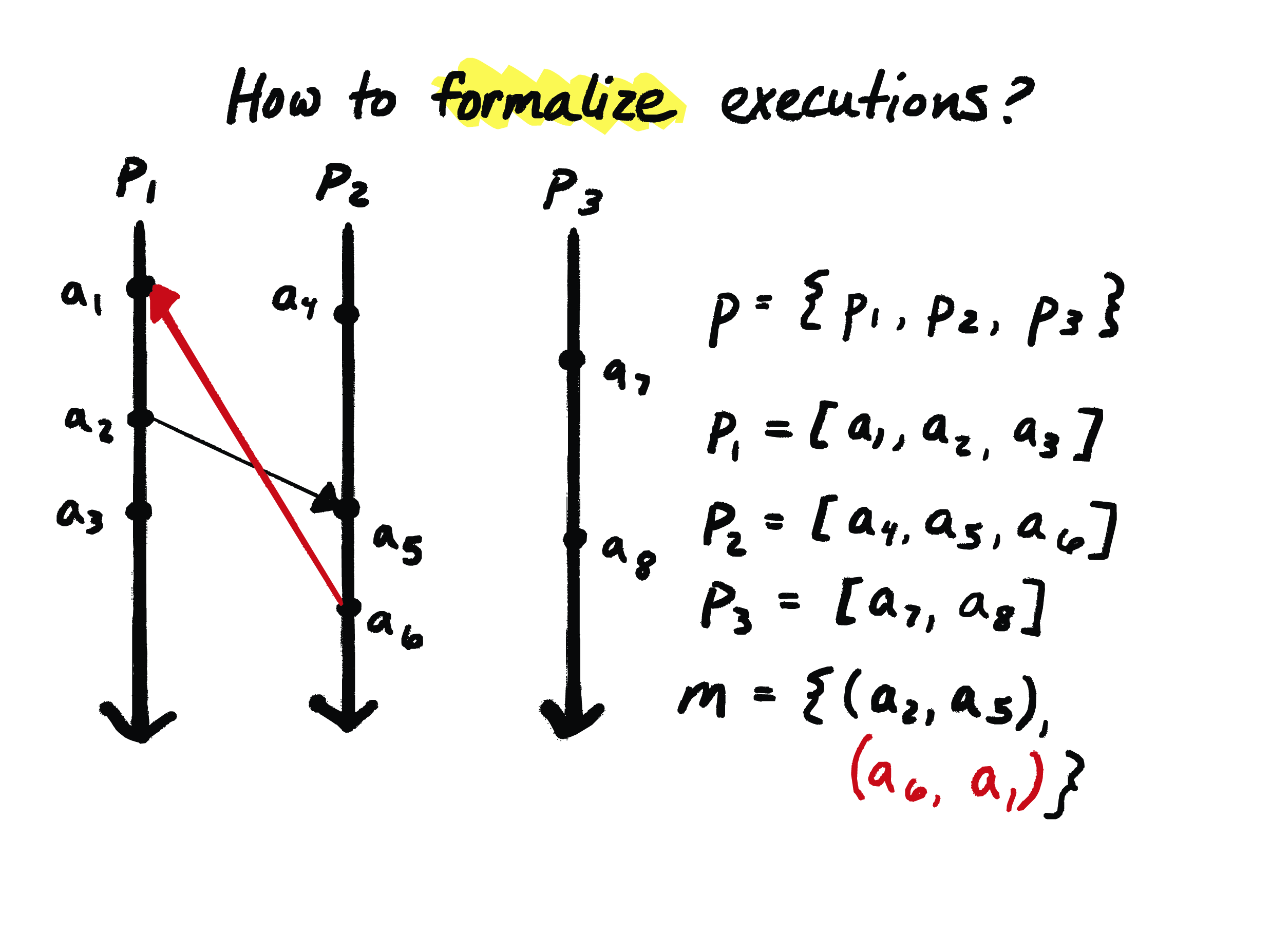

One issue is that this representation, doesn’t stop you from representing something that’s actually physically impossible, like a causal loop. So here, \(a_2\) is the send event for this message, \(a_5\) is the receive event, and then later on process 2, we have a send event for a message that’s being sent backward in time, back to \(P_1\). So this is an execution that couldn’t actually physically happen, and the structure of our data doesn’t really help us avoid this situation. The formalism will still let us write down this execution that couldn’t actually occur, and you would need to do some additional checking to make sure that your data is self-consistent.

The other problem is that this representation doesn’t stop you from representing what are called inconsistent cuts.

So, a consistent cut in an execution like this is something like this blue line with a happy face here. It’s separating the events of the execution into a clear past and a clear future. So, here, the “past” is what’s above this blue line, and the “future” is below it. And if an event is on the “past” side of the cut, then if it’s a consistent cut, then everything that’s causally before that event is also on the “past” side of the cut. And this blue cut is in fact a consistent cut.

An inconsistent cut, like the one represented by the red line here, fails to have that property. So here, for instance, we have this event \(a_5\), which is on the past side of this cut – but \(a_5\) represents the reception of a message that was sent here at \(a_2\), which is actually on the future side of the cut. So \(a_2\) should causally precede \(a_5\), but \(a_2\) is on the future side of the cut.

So the traditional model doesn’t help us avoid inconsistent cuts. And so, if I just take a prefix like this of the events on each process, well, it might be a consistent cut or it might be an inconsistent cut. And the problem is that there’s no connection between the processes that we’re splitting into past and future, and the messages we need to respect.

So you might have heard of this famous software development dictum “make illegal states unrepresentable”, which I think is due to Yaron Minsky. As my student Jonathan put it, this way of representing executions makes illegal states all too representable.

Okay, so what do we do about this? What should we do instead?

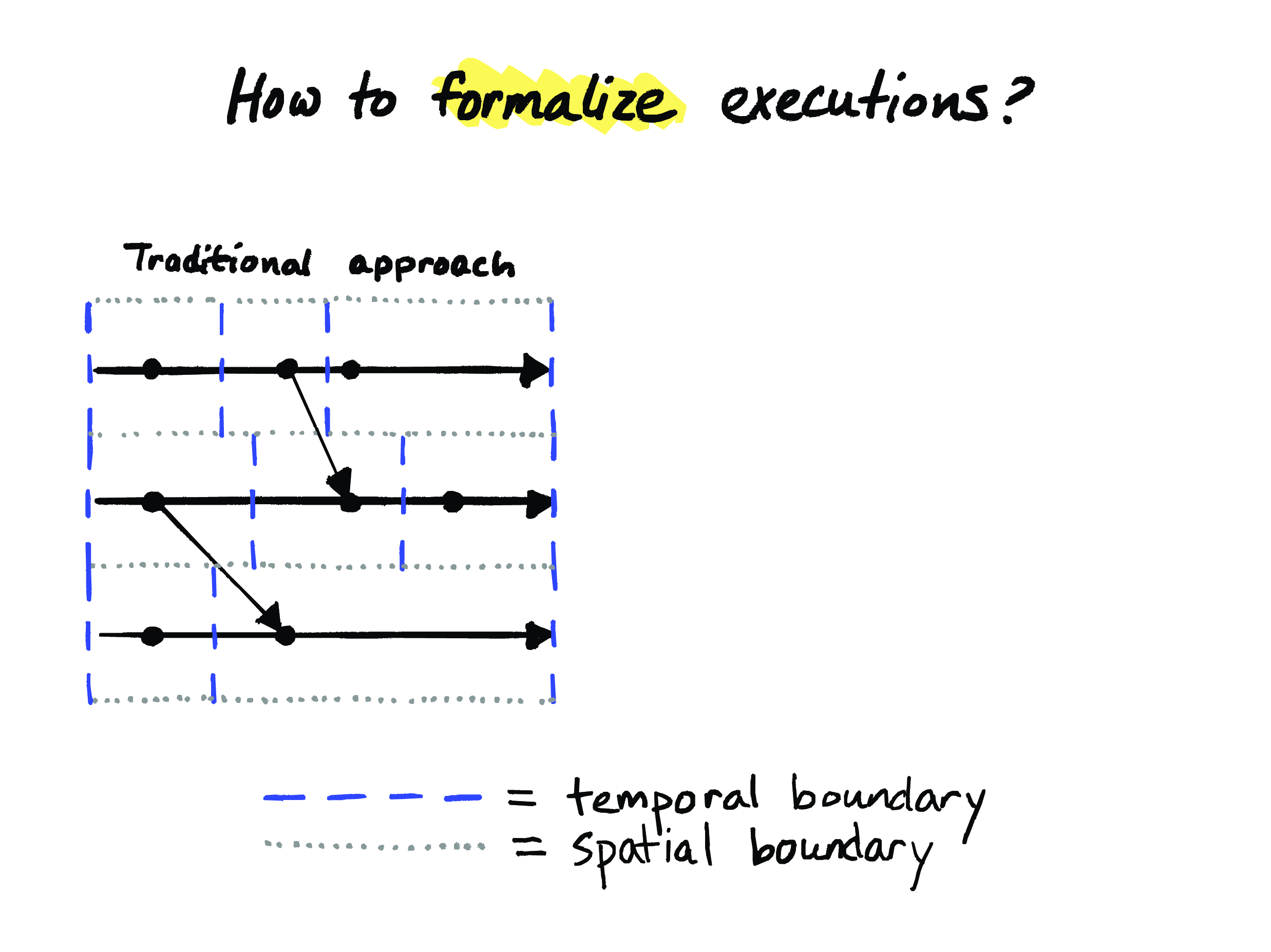

To get a better idea of what’s problematic about the traditional approach to representing executions, let’s take a closer look at it. So here I’ve written down the same execution we were looking at before. I’ve turned the diagram on its side, and kind of flipped it around, and I’ve removed the labels on events. But it’s the same execution as before; it’s got the same structure.

The only difference is that I’ve added some additional dotted gray and dashed blue lines to this diagram, which make the structure of the execution more explicit. So, in this traditional approach, the top-level structure of this execution is this collection of processes, so the first thing we have to do is visually separate these processes from each other. And that’s what these dotted gray lines do. And we can think of them as spatial boundaries between the processes.

And next, each of these individual processes has a sequence of events in time. And we can make that explicit too, by adding these dashed blue lines as temporal boundaries between events.

Unfortunately, we cannot really do the same thing with messages. Because we made the order of events within a process our top priority, messages are kind of a different kind of entity. But notice how these message arrows always seem to cross these gray “spatial” boundaries, which run horizontally. They cross those rather than crossing the blue “temporal” boundaries, which run vertically. So these process-local edges that cross over the dashed blue lines are inherently causally ordered by the structure of the data, but the edges that cross over the dotted spatial boundaries between processes are not inherently causally ordered by the structure of the data. And that is what makes it possible to accidentally construct an inconsistent cut.

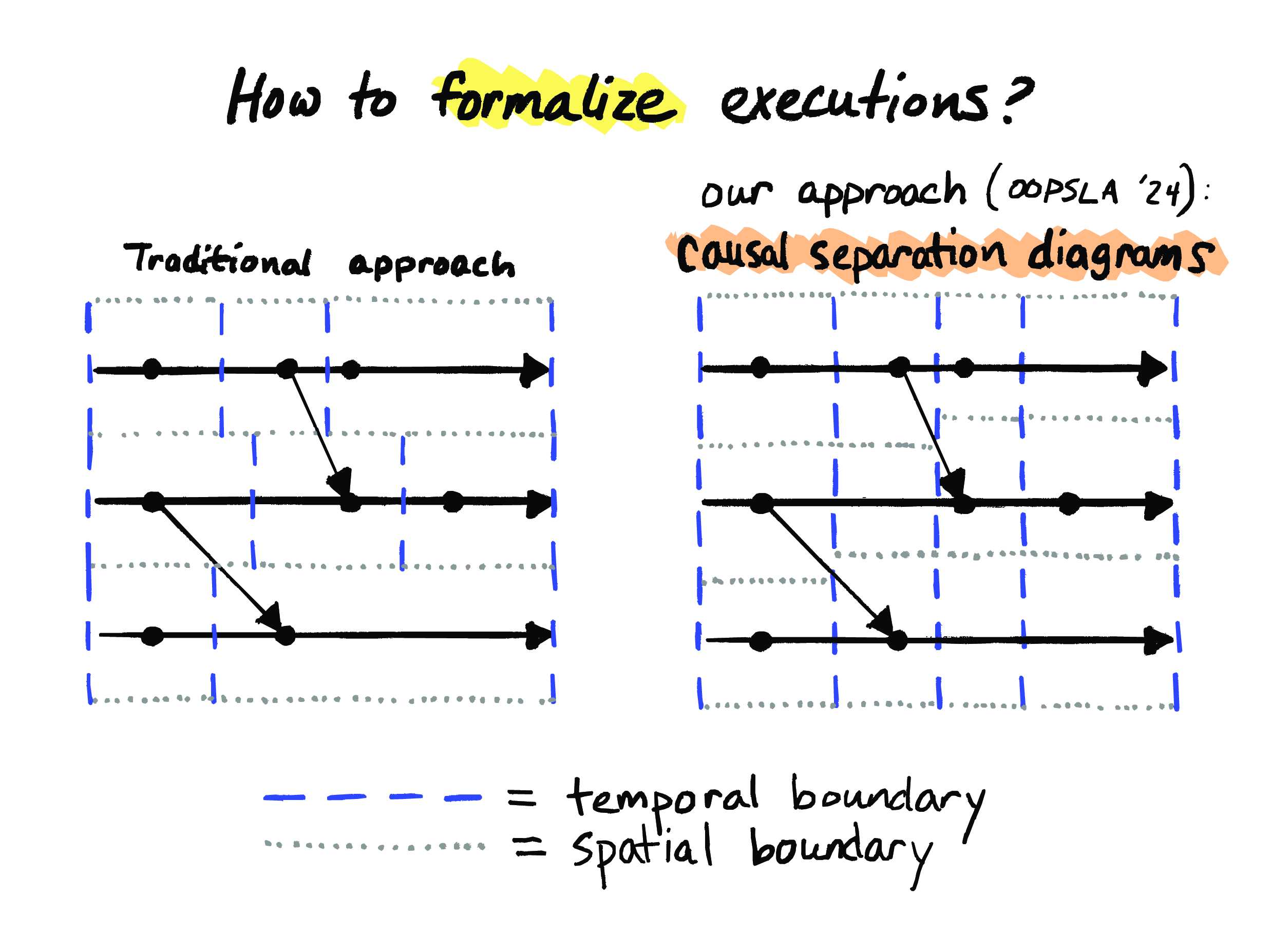

So, this happened because we prioritized the spatial boundaries first, instead of prioritizing the temporal boundaries. What would happen if we did it the other way around? What would happen if we laid down the temporal boundaries first, and then the spatial ones?

That’s exactly what our approach does. So here’s that same execution again, but now represented using one of our diagrams, which we call “causal separation diagrams”. So, it’s the same execution, but represented in a different way.

First, we’re laying down enough consistent cuts to separate every event. That’s what these vertical dashed blue lines are. So, instead of splitting up by processes first, we’re splitting up this execution into these global time steps, where by “time” I mean logical time. And then, within each of these global time steps, we can add these spatial boundaries between each distinct location.

And we end up with this different way of decomposing our diagram. So the original way of decomposing it, we had this structure that consisted of these three separated sequences of events. In our new decomposition, we have a single sequence, not of events but of “global steps”. And then those global steps, which are these columns here, delimited by these dashed blue lines, those are each made up of “local steps” delimited by the spatial boundaries.

So here we’ve got four big global steps arranged from left to right, separated by the blue dashed lines, and then every global step happens to contain three local steps, separated by these gray dotted lines.

So, this choice, to prioritize the temporal boundaries over the spatial boundaries, is the fundamental difference between our approach – CSDs – and the traditional model. And everything else is just a consequence of that. And I’ve been saying “temporal” boundaries, but I could also just as well have called them causal boundaries, because this potential causality here is following the flow of time. Hence the name “causal separation diagrams”.

What’s most interesting here is that both messages and processes now evolve over causal boundaries. Information never crosses directly across a spatial boundary. And as a consequence of that, a diagram that can be decomposed this way necessarily has no causal loops. In other words, if we can construct diagrams this way with a CSD, then they are necessarily going to be causal by construction. So we have made illegal states unrepresentable.

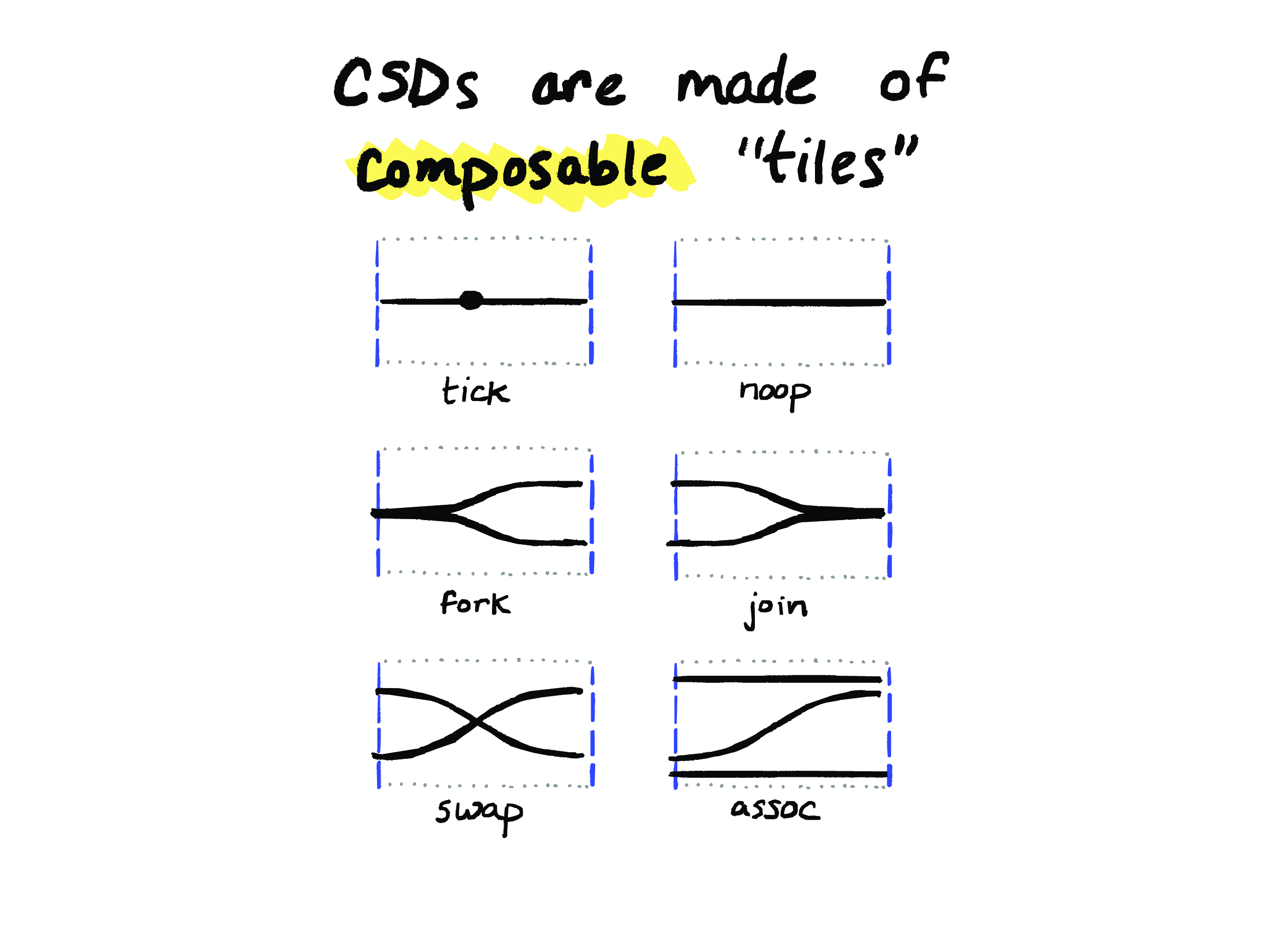

Here are all the different kinds of local steps that we can build diagrams out of. In the first two here, a tick is just a local event on a process, and a noop is the absence of an event.

These last two – swap and assoc here – they don’t model any actual events. Instead, they just allow us to rearrange the wires through the diagram so that processes can communicate with more than just their immediate neighbors. You can think of these as sort of like structural rules in a logic.

And the middle two – fork and join – these are modeling the two halves of a traditional message. But unlike in a traditional message, we have both the process and the message state that are coming out the right-hand side, rather than having the message go out the top or bottom.

So, in fact, our model doesn’t distinguish process state from message state at all! Nothing prevents a so-called “process” from joining state with another process, or a local event from occurring on a message. So we’re referring to these inputs and outputs uniformly not by “processes” or “messages”, but by “sites”. A site is just a place where state can exist. This was my student Jonathan’s innovation, and it took me a while to get my head around treating messages and processes as the same thing, but it actually makes sense to me now. So a process sending a message is just a site forking off a piece of its state out into the world as a new site, and a process receiving a message is just two sites joining together.

So now that we have these tiles, these composable tiles, we can stick them together however we like and get a consistent CSD. And I’ve left it out here for brevity, but each one of these tiles actually has a type, which says how we’re allowed to compose it with other tiles. And we also have combinators for composing local steps into global steps, and for chaining global steps together into an execution. And the type of each tile tells you how it can be composed with other tiles vertically and horizontally. And for the fancy type enthusiasts here: yes, these are dependent types!

So, okay, so what does all this have to do with interpreters, which is the topic of this talk? So, earlier, when we were talking about what interpretation meant, I said that if we say that a syntax is interpretable, that usually means that the interpretation of a given input is determined by the interpretations of its subcomponents. And to do that, we need to have an obvious way to break down the input into subcomponents and to put it back together. The “obvious way” to break things down and put them back together is what we call an induction principle.

So, for that traditional formalization of executions that I showed first, we unfortunately don’t have a nice induction principle for the thing on the left here; we just have a set of processes and a set of messages, and the structure of the data doesn’t tell us how we’re supposed to break things down and put them back together. So executions that are represented in this traditional way on the left are not particularly amenable to interpretation – not if we want to work in a tool that encourages us to inductively define data structures, especially like a mechanized proof assistant.

But on the other hand, executions that are represented as causal separation diagrams come with a lovely induction principle, since they’re actually just lists of global steps. So, to take a CSD apart, you can just peel off one global step at a time; to put it back together you can just glue on one global step at a time. And this makes CSDs amenable to interpretation.

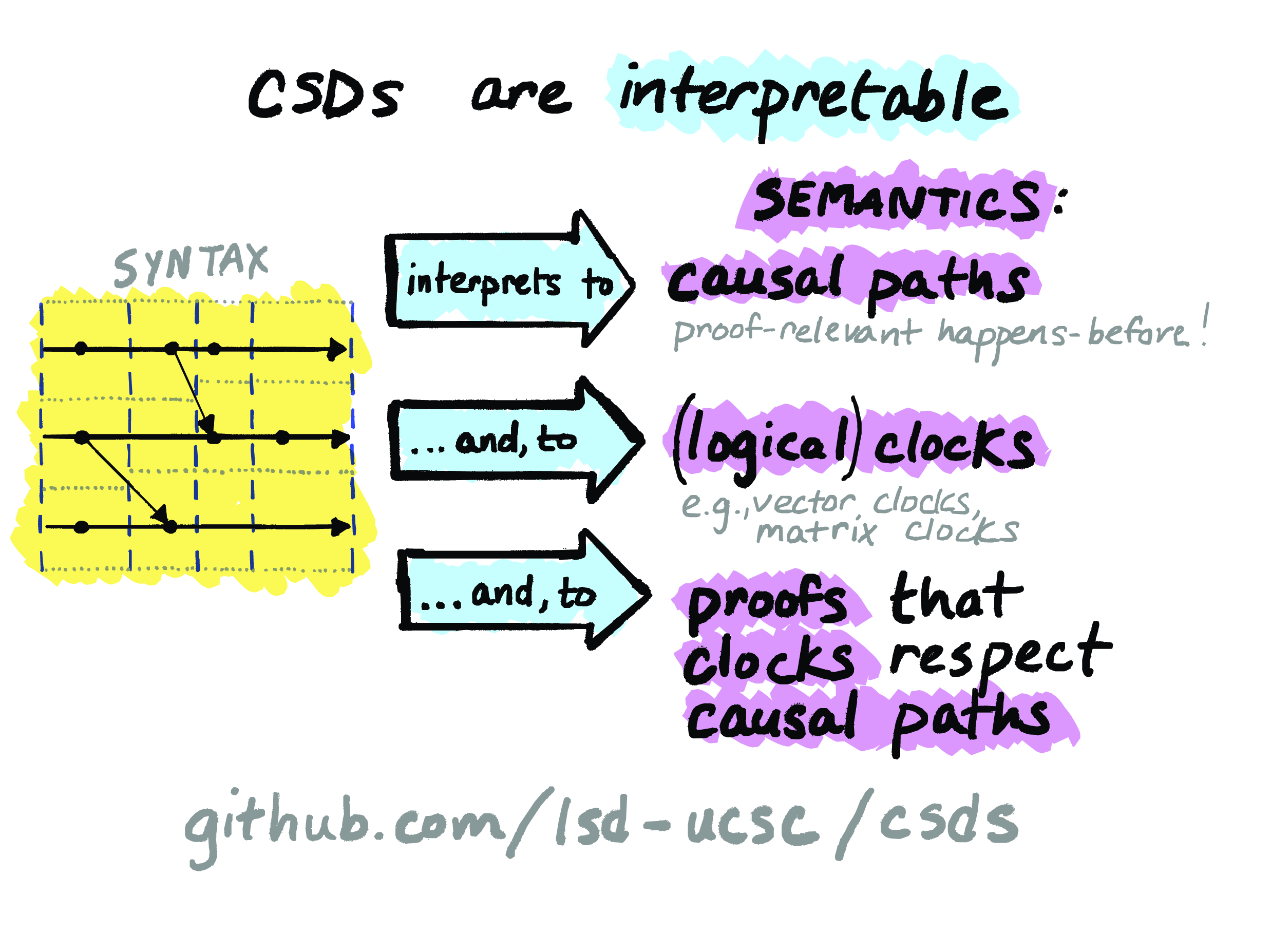

So, CSDs give us a formal, graphical, inductively defined syntax for representing concurrent executions, and that’s something that we can straightforwardly write interpreters for. So that’s exactly what we do. In our paper we talk about three ways to interpret CSDs – that is, three ways of giving CSDs a semantics!

The first of these is an interpretation of CSDs into what we call causal paths. Causal paths are nothing but a proof-relevant analogue of the classic Lamport happens-before relation. So, instead of just saying that two events are causally related or aren’t causally related, we can interpret a CSD into a dependent type of the causal paths through a diagram, and these paths give evidence of the causal relationship between events.

The second way that we interpret CSDs is into logical clock functions, which assign an event to its corresponding logical timestamp. So there are a lot of different kinds of logical clocks that get used in distributed system implementations: Lamport clocks, vector clocks, matrix clocks – our interpretation is parametric in a choice of clock implementation, so you can instantiate the same machinery over many logical clocks, and we’ve done that for a bunch of different flavors of clocks.

And the third way that we give to interpret CSDs is into proofs that clocks respect causal paths. So a logical clock that respects causal paths is a clock that satisfies Lamport’s clock condition, which is the thing that makes a logical clock a logical clock. So using CSDs, we’re able to give a mechanized proof of the clock condition that’s parametric in the choice of clock. This interpretation-based approach to verification of clocks would be really awkward and difficult if we didn’t have this inductive data structure that accounts for causality; but with CSDs, it just kind of falls out naturally.

So, to wrap up this part, I’ll just mention that you can find our proof development on GitHub – this is done in Agda – and my student Jonathan and I are actively looking for more things to use CSDs for, which I’d love to talk with folks about.

Conclusion

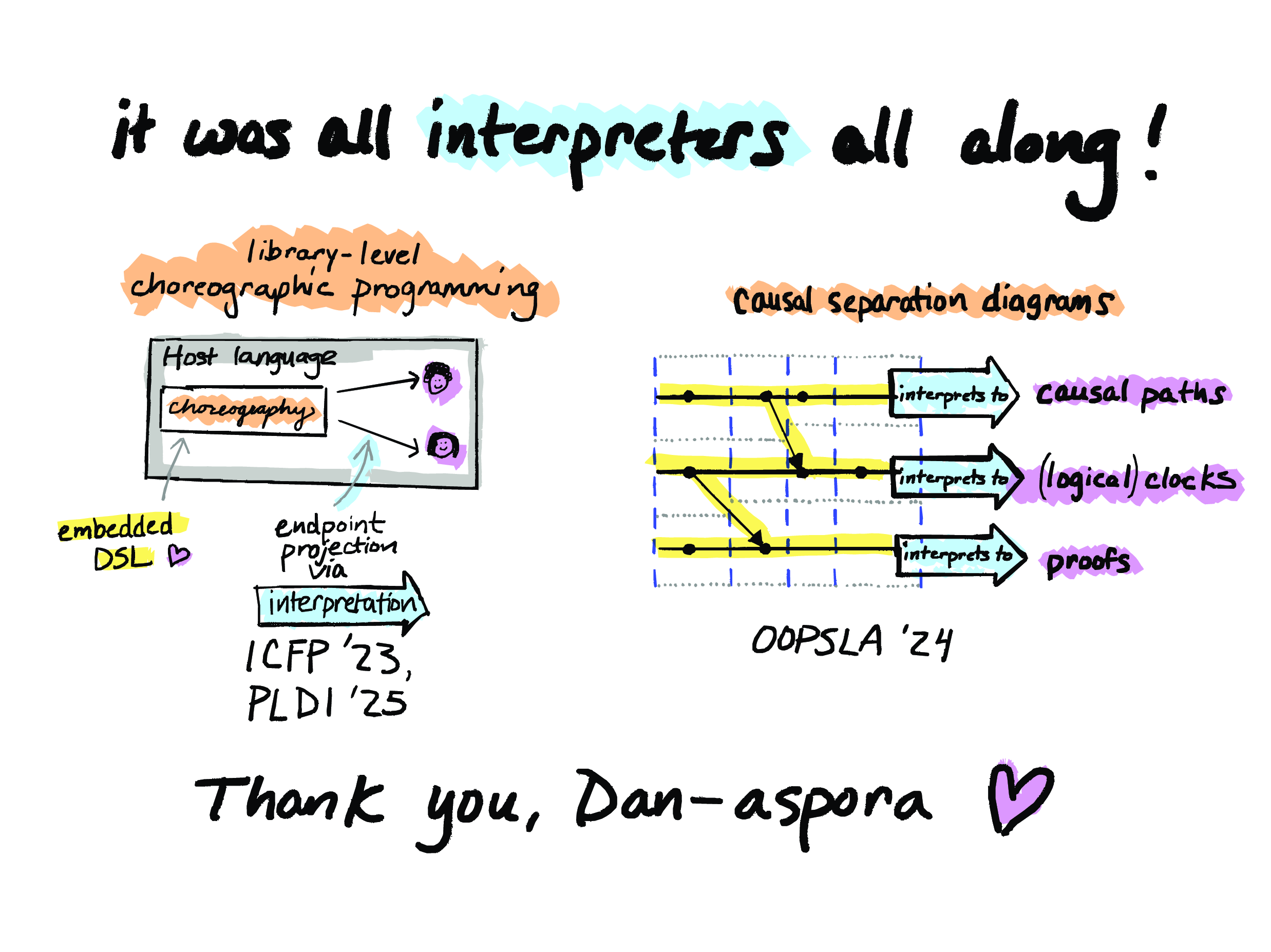

Okay, so, we’re almost at the end. So, to sum up: I’ve talked about two lines of work from my research group that turned out to be all about interpreters, all along.

So we talked about library-level choreographic programming, which lets programmers write distributed programs as single, unified programs in their favorite language, and then dynamically project them to multiple endpoints.

And we talked about causal separation diagrams, which are inductively defined data structures designed for elegant mechanized reasoning about happens-before relationships in concurrent executions.

But really, we could sum up these two lines of work as being about interpreters. HasChor is just asking, “What if endpoint projection was an interpreter?” and CSDs are just asking, “What if you could write interpreters for Lamport diagrams?”

So the takeaway I have for you here is: you can’t go wrong by studying how interpreters and interpretation work. And then go study something else, and reap the benefits of applying your knowledge to that new domain.

So that’s all I’ve got, and I want to thank you for your attention!

Comments