Conflict resolution in collaborative text editing with operational transformation (Part 1 of 2)

by Abhishek Singh · edited by Austen Barker and Lindsey Kuper

Introduction

Anyone who has used a version control system or collaboratively edited a document knows all too well the problems that arise when versions of a document conflict. Suppose Alice and Bob decide to collaborate on a document. Alice creates a new document, shares it with Bob, and starts editing. Meanwhile, Bob edits his copy. If Alice and Bob’s respective copies of the document magically synchronized with each other with zero latency, collaborative text editing would be easy. But if there is any latency between Alice and Bob — perhaps due to a network partition — then their copies of the document may diverge, leading to a conflict that must eventually be resolved.

If Alice and Bob had been writing on paper, they would have to manually create a unified document incorporating both their changes. Collaborative software — encompassing both real-time collaborative editing tools such as Google Docs, and version control systems such as Git, Mercurial, and Subversion — aims to automate as much of this conflict resolution process as possible.

Operational Transformation

Operational transformation is an algorithm first discussed in a 1989 paper called “Concurrency control in groupware systems” by Ellis and Gibbs and intended to allow systems to collaboratively perform a common task. The technique allowed users keep track of operations performed on shared data as a means of keeping track of changes in the data. Additionally, it formalized certain properties functions must have to allow tasks to be performed collaboratively. A more thorough survey of operational transformation was published by Sun and Ellis in 1998. The technology grew beyond Ellis and Gibb’s original definition and now describes a host of architectures, data models and algorithms for building collaborative software systems. For the rest of this post, we will restrict ourselves to operational transformation as described in the original paper, and its use in collaborative text editing.

Operational transformation was popularized by Google in its Google Wave project. Since Google Wave was discontinued, some of the original papers and definitions can be hard to find, but some documents are available via the Wayback Machine. Operational transformation has also made it into Google’s other products, such as Google Drive and Google Docs.

The Google Wave project itself was based on the Jupiter collaboration system. Jupiter was aimed towards simplifying the algorithm created by Ellis and Gibbs by creating a centralized architecture, as opposed to the free-range collaborative system that Ellis and Gibbs drew out in their paper. In our discussion we deal with the decentralized idea as presented in Ellis and Gibbs’ original 1989 paper. To be specific, we look at the Distributed Operational Transformation (dOPT) algorithm and its use in Ellis and Gibbs’ GROVE editor.

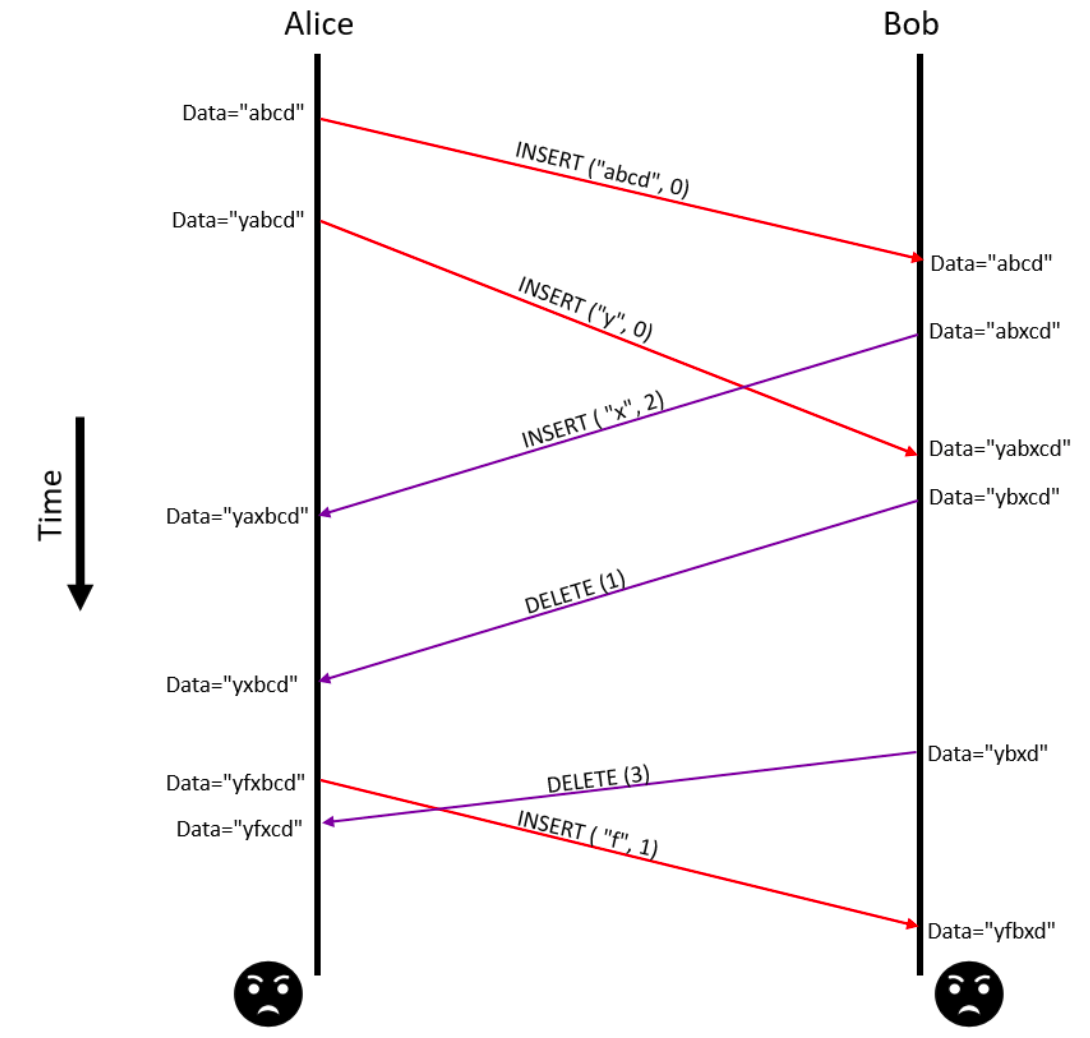

To describe the problem in in its most basic form, let’s say we have a document which is being edited by two users, Alice and Bob. Alice creates a local copy of the document with the string abcd and shares it with Bob. She then starts editing the document, and these changes are shared with Bob as shown in the figure below.

In Figure 1, the red arrows denote operations performed by Alice on her local copy of the data and then their subsequent transmission to Bob for synchronizing their data. The purple arrows show operations executed by Bob on his copy of the data and then transmitted to Alice. For example, Alice inserts y at index 0 in the string with the operation INSERT ("y", 0), and Bob inserts x at index 2 with INSERT("x", 2), then deletes the character at index 1 with DELETE(1). Any changes that either Alice or Bob make to their copy of the document is sent over to the other as an operation message.

The problem is that neither user applies the operation to their local data with any consideration of how the other user applied the operation at their end. Clearly, the data on which Alice executes an operation is not the same as the data on which Bob applied the same operation. The problem is that indices used by Alice do not always correspond to the indices used by Bob. This leads to data inconsistencies at both ends when operations are executed by either of them.

A mechanism is clearly needed that will allow Alice to correctly apply the the operations that Bob did on his data, and vice-versa. The dOPT algorithm specifies the properties of a transformation function which could help us transform the operation and indices received from one user and apply it safely on the other user. Next, we will discuss a rudimentary implementation of such a transformation.

An example of collaborative editing using distributed operational transformation (dOPT)

For this blog post, I wrote a simple Go program and a set of test cases which showcase dOPT. The implementation follows the algorithm roughly as stated in the 1989 paper by Ellis and Gibbs.

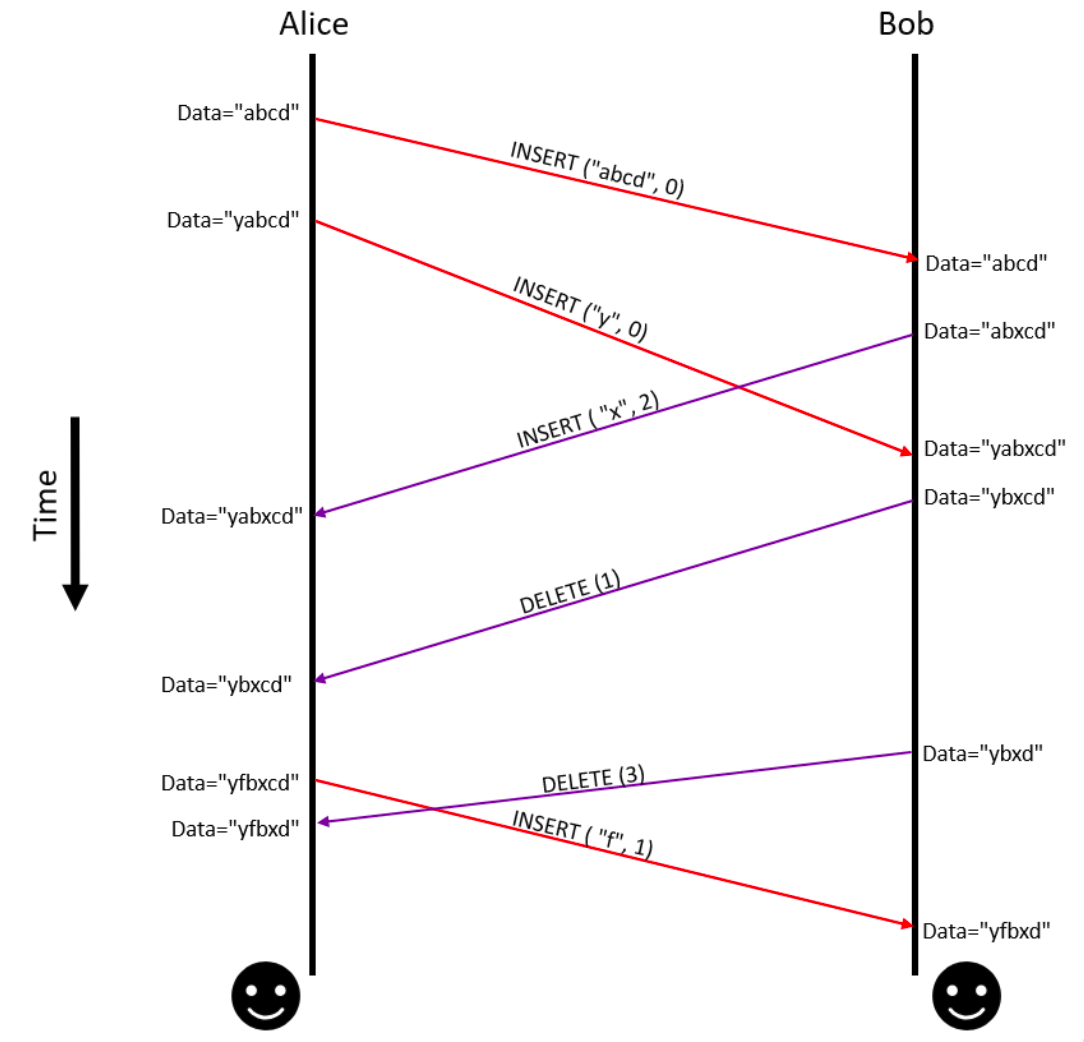

To see what the code does, let’s begin by walking through the example shown in the figure below. Again, Alice and Bob have a shared document that both start editing. At the end of each edit, the edit operation performed is sent to the other. When a message is received, the indices are recomputed based on some criteria and the correct operation is executed.

As seen from Figure 2, the following operations are performed by Alice and Bob:

- Initially, the data is

abcd, inserted by Alice and sent over to Bob. Alice and Bob have the same data and are in a consistent state. - Alice inserts a

yat index0on her copy of the data that now becomesyabcd. This operation is then sent to Bob as well. - While Alice was performing the insert in step 2, Bob inserts

xat index2to his copy, which isabcdas of this moment. This happens concurrently with the operation in step 2. The insert modifies Bob’s local copy toabxcd. Bob then sends this operation to Alice. - Bob then receives Alice’s operation from step 2, correctly computes the index of the operation on his copy of the data, and executes the operation on his copy, which is modified to

yabxcd. - Bob’s insert operation from step 3 is received by Alice at some point and Alice correctly computes the index for the

xto be inserted on her local data. Her local data is nowyabxcd— the same as Bob’s. - If this were the end of the editing process, Alice and Bob would both find that their local copies are now consistent. But they don’t stop. They continue editing their copies, and every edit and subsequent transmission to the other keeps their local data consistent with the others.

- Bob deletes the character at index

1from his copy of the data, which wasyabxcd, modifying it toybxcdand sending this information to Alice. - When Alice receives the delete operation from Bob, she correctly computes the indices and modifies her copy to

ybxcd. - While Alice is executing the operation in step 8, Bob deletes a character at index

3of his local data, which isybxcd, changing it toybxdand sending this operation over to Alice. - At some point after Alice executes step 8 but before receiving the message from Bob from step 9, Alice inserts

fat index1to her local copy, modifying it fromybxcdtoyfbxcd. - The operation from step 9 is received by Alice, who deletes the character from her index

4, with the data finally becomingyfbxd. - Meanwhile, Bob receives Alice’s insert from step 10 and updates his copy to now read

yfbxd.

There are some things that should be noted from both Figure 2 and its explanation above. First, steps 2 and 3 in the above discussion are concurrent. There is no way to know when exactly steps 2 or 3 were executed by either parties. We can however state unequivocally that step 2 happened before step 5 at Alice’s end (and for Bob, step 3 happens before step 4). Thus, at their own ends, operations are executed sequentially, whereas some operations are concurrent when we look at the system as a whole.

Based on Figure 2, we create a set of test cases that will be the basis of further discussion of the process. In my implementation, I make a few assumptions that differ from the dOPT algorithm described in Ellis and Gibbs’ paper:

- Operation messages from either sites are received exactly once.

- There are exactly two editors in the system: one at Alice’s end and the other at Bob’s end.

- My implementation does not use clocks to timestamp operations, so the happens before relationship is established based on message delivery. It is assumed that LOCAL and REMOTE operations happen concurrently.

- Operations are processed in the order in which they are seen and executed at a particular site. In our implementation the executed operations are stored in a list

OTEditor.Ops. - Unlike the implementation in the paper, we do not assign priorities to an operation. Every operation has equal priority.

- An operation is sent to others immediately after it was executed at one particular site. There is no out-of-order delivery of messages.

One of the main issues in this implementation is that we overlook establishing causality between operations. There is an implicit happens before relationship established by the order in which operations are stored in the OTEditor.Ops list. This can easily be broken by packets that arrive out of order, leading to data inconsistency. Suppose Bob performs two operations Op1 and Op2, and Op2 reaches Alice before Op1; this would cause data inconsistency in my implementation of dOPT, since the transformation depends on the previous operation to compute the new indices.

The code below shows test cases based on the operations performed in Figure 2. The comments in the program identify the operations and the generator of the operations.

func TestOTEditor_Transformation(t *testing.T) {

ot := OTEditor { Data: "yabcd", Ops: []Op{

// OPERATION #1 : ALICE

{Data: "abcd", Index: 0, Location: LOCAL, Op: INSERT},

// OPERATION #2 : ALICE

{Data: "y", Index: 0, Location: LOCAL, Op: INSERT},

},

}

// OPERATION #3 : BOB

fmt.Println("Operation 3. BOB (remote) insert 'x' at index 2")

ot.AppendOperation(INSERT, "x", 2, REMOTE)

assertEquals(ot.Data, "yabxcd")

// OPERATION #4 : BOB

fmt.Println("Operation 4. BOB (remote) delete char at index 1")

ot.AppendOperation(DELETE, "", 1, REMOTE)

assertEquals(ot.Data, "ybxcd")

// OPERATION #5 : ALICE

fmt.Println("Operation 5. ALICE (local) insert 'f' at index 1")

ot.AppendOperation(INSERT, "f", 1, LOCAL)

assertEquals(ot.Data, "yfbxcd")

// OPERATION #6 : BOB

fmt.Println("Operation 6. BOB (remote) delete char at index 3")

ot.AppendOperation(DELETE, "", 3, REMOTE)

assertEquals(ot.Data, "yfbxd")

}

Ordering of the operations is implicit in the test cases. Operations are executed from the perspective of Alice in Figure 2, and are processed in the order in which they are seen by Alice.

In the code, an OTEditor is represented by a Data string and a list of operations, Ops, that have taken place on it. There are two supported operations: INSERT and DELETE. LOCAL and REMOTE are constants distinguishing two operation locations; LOCAL operations should be thought of as being performed on a local copy of the data, while REMOTE operations should be thought of as being performed by another user (Bob in this case) on their own copy of the data and sent over as part of the synchronization process. At the end of each operation execution, data at both Alice and Bob’s end is synchronized and is in a consistent state.

Running the tests produces the following output, including log messages produced by calls to AppendOperation:

Operation 3. BOB (remote) insert 'x' at index 2

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Existing Data: {yabcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0}]}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 New Operation received: {1 x 2 1}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Executing new operation: {1 x 2 1}, current data: yabcd

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Current value of data: {yabxcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1}]}

Operation 4. BOB (remote) delete char at index 1

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Existing Data: {yabxcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1}]}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 New Operation received: {2 '' 1 1}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Executing new operation: {2 '' 1 1}, current data: yabxcd

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Current value of data: {ybxcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1} {2 '' 1 1}]}

Operation 5. ALICE (local) insert 'f' at index 1

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Existing Data: {ybxcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1} {2 1 1}]}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 New Operation received: {1 f 1 0}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Executing new operation: {1 f 1 0}, current data: ybxcd

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Current value of data: {yfbxcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1} {2 1 1} {1 f 1 0}]}

Operation 6. BOB (remote) delete char at index 3

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Existing Data: {yfbxcd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1} {2 1 1} {1 f 1 0}]}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 New Operation received: {2 '' 3 1}

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Executing new operation: {2 '' 3 1}, current data: yfbxcd

2018/11/12 15:15:46 Current value of data: {yfbxd [{1 abcd 0 0} {1 y 0 0} {1 x 3 1} {2 '' 1 1} {1 f 1 0} {2 '' 4 1}]}

In the paper, a necessary (but not sufficient) condition to ensure that the transformation function works is commutativity of the operations. When dOPT is applied commutativity of operations must be ensured. Additionally, we need to understand if transformation is required. Transformation in the paper is a technique to resolve conflicts. If there are no conflicts, we do not apply any transformations.

First, we need to understand when a transformation is not required. In the above test case, we have three cases where transformation is not required.

- During the execution of operation #2 where

LOCAL(or Alice) insertsy. These areLOCALoperations. Data consistency is ensured because theLOCALeditor is “reading your writes”. - Operation #4 does not require any transformation because the last operation (#3) was also a

REMOTEedit. Since there were no other edits performed anywhere between operation #3 and #4, the data is consistent at both Alice and Bob’s end before the execution of operation 4 (check Figure 2). - Operation #5 does not required transformation because execution of #4 synchronized edits at both

LOCALandREMOTEends.

In all of the three cases, there are no conflicts where a transformation function is needed. The only case where transformation is required is when the last operation was LOCAL and the current operation is REMOTE. This is because the remote user (Bob) may not be aware of the last operation performed by the local user (Alice) when he made the edit. This rule must be taken with a pinch of salt as it is specific only to this implementation as there exist only two editors in the system.

Next, we discuss what commutativity is and how it applies to our test cases. Given two operations A and B, the transformation T generates the following transformations:

- B’ := T (B, A)

- A’ := T (A, B)

The transformation T is implemented such that B x A’ = A x B’. Here the symbol x in the expression is used to refer to order of operation execution. For example, for operations A and B, A x B means apply operation A, then B.

The symbol = in LHS = RHS refers to the fact that data after application of RHS operations equals LHS.

This transformation works in the test case shown above. Let’s first consider operation #3:

- A :=

INSERT ("y", 0 ); operation #2. - A’ :=

INSERT ("y", 0 ); The transformation is the same A, as operation #1 wasLOCAL. - B :=

INSERT ("x", 2 ); operation #3. - B’ :=

INSERT ("x", 3 ); the operation after the transformation. - Data at both ‘remote’ and

LOCALsystems before operations A and B isabcd. - B

xA’ yields dataabxcdandyabxcd. - A

xB’ yields datayabcdandyabxcd. - Both sequences of operations lead to the same state after test case #1, so commutativity holds.

Updates by operations #4 and #5 are all conflict-free and do not require transformation. Operation #6 does. To prove commutativity for operation #5 and #6:

- A :=

INSERT ("f", 1 ); operation #5. - A’ :=

INSERT ("f", 1 ); operation #4 did not violate consistency , no transformation required. - B :=

DELETE ( 3 ), operation #6. - B’ :=

DELETE ( 4 ), operation after the transformation. - Data at both ‘remote’ and

LOCALsystems before operations A and B isybxcd. - B

xA’ yields dataybxdandyfbxd. - A

xB’ yields datayfbxcdandyfbxd. - Again, both sequences of operations lead to the same state.

The case of concurrent local and remote updates is the only case where conflict resolution is needed, and therefore the cases discussed above ensure that the transformations produced are always commutative.

The index recomputation algorithm

As mentioned in the previous section and discussed in the test case above, indexes are recomputed when operation messages are received by either Alice or Bob. We now discuss how the index recomputation is performed. The index recomputation follows the following rules:

- Deletion is performed one-character-at-a-time in this implementation.

- We maintain a list containing the previously executed operations. This list maintains the order of the sequence of operations that have been executed.

- As discussed previously, transformation is required only when the locations of the current and last operation differs: last operation was

LOCALand currentREMOTE, or vice-versa. - When transformation is required, we check the index of current and last operations, and the operation types. Operation types in our implementation can be either

INSERTorDELETE. - If

currentOperation.Index > lastOperation.IndexANDlastOperation.Type == DELETE,currentOperation.Index = currentOperation.Index - 1. - If

currentOperation.Index > lastOperation.IndexANDlastOperation.Type == INSERT,currentOperation.Index = currentOperation.Index + length (lastOperation.Data).

Indices are recomputed in steps 4 and 5. In both these steps, indices are recomputed only if the index of the current operation is greater than that of the last operation. This is done because only in this case can the current operation alter the consistency of the data.

Suppose the data before the “last operation” executed was abcd and the “last operation” was INSERT (“x”, 3). Data after the execution of the “last operation” is abcxd. Now suppose the “current operation” had an index of 2. Regardless of what exactly the operation is, it is clear that it can be applied without any need for index recomputation, as there is no offset in the index of the “current operation”, whatever that operation might be.

Let us now suppose that (beginning with the same initial data abcd) the “last operation” was DELETE(2). After the execution of the “last operation”, the data is modified to abd. If the “current operation” has an index of 3, it can be seen in this example that there is no index 3 in the data after the execution of the “last operation”. In this case, there is a need to offset the index of the “current operation” before it can be applied. To offset the index, we depend on the type of the current operation. If the “last operation” was an INSERT, the “current operation”’s index must be offset by the length of the data, which was inserted by adding the index of the “current operation” with the length of the data in the “last operation”. If the “last operation” was DELETE, the current index is offset by 1 (as we only allow deletion one character at a time).

Editor implementation

Now that expectations are set, we implement a simplified operational transformation editor. We continue borrowing language from our previous discussion based on Figure 2. The first part of the implementation deals with setting up data structures. We have two main operations: INSERT and DELETE. These operations can be done either locally (by the same process where the program is executing) or could be sent as a synchronization message from a another process ( or remote user). Operations are tagged LOCAL if they are performed by the process executing the program (Alice) and tagged REMOTE if they are sent from another process (Bob). The operations are described by the struct Op, which defines the structure of the operations which the editor (OTEditor) can process. The editor OTEditor itself has two fields: Data, which stores application data, and Ops, which keeps a record of operations that have been processed by the OTEditor.

type Operation string

const (

INSERT Operation = "1"

DELETE Operation = "2"

)

type OpLocation int

const (

LOCAL OpLocation = 0

REMOTE OpLocation = 1

)

type Op struct {

Op Operation

Data string

Index int

Location OpLocation

}

type OTEditor struct {

Data string

Ops []Op

}

The OTEditor has several methods that implement Operational Transformation. The AppendOperation method is called whenever a new operation is performed by the user (either remote or local). All operations are added to the OTEditor.ops slice (think of it as an list). The data is stored in the OTEditor.Data field. When AppendOperation is called, the OTEditor performs a transformation as previously discussed to compute the new value of the index where the data has to be inserted or deleted. This transformation is performed in the performTransformation method.

The AppendOperation and exec methods are straightforward, and we will not spend too much time on them except to note that exec modifies the OTEditor.Data field according to the operation that needs to be performed. Before modifying the Data field, exec calls performTransformation.

func (c *OTEditor) AppendOperation(op Operation, data string, index int, opLocation OpLocation) {

operation := Op{Op: op, Data: data, Index: index, Location: opLocation}

log.Printf("Existing Data: %v\n", *c)

log.Printf("New Operation received: %v\n", operation)

c.exec(operation)

}

func (c *OTEditor) exec(operation Op) {

log.Printf("Executing new operation: %v, current data: %s\n", operation, c.Data)

// Recompute indices for the operation

c.performTransformation(&operation)

b := []byte(c.Data)

status := false

switch operation.Op {

case INSERT:

if len(b) <= operation.Index {

log.Printf("Cannot perform operation %v, index out of bounds.", operation)

} else {

b1 := b[0:operation.Index]

b2 := []byte(operation.Data)

b3 := b[operation.Index:]

var b0 []byte

finalData := append(b0, b1...)

finalData = append(finalData, b2...)

finalData = append(finalData, b3...)

c.Data = string(finalData)

status = true

}

case DELETE:

if len(b) <= operation.Index {

log.Printf("Cannot perform operation %v, index out of bounds.", operation)

} else {

b1 := b[0:operation.Index]

b3 := b[operation.Index:]

var b0 []byte

finalData := append(b0, b1...)

finalData = append(finalData, b3[1:]...)

c.Data = string(finalData)

status = true

}

}

if status {

ops := append(c.Ops, operation)

c.Ops = ops

log.Printf("Current value of data: %v", *c)

}

}

The performTransformation method implements the heart of the application. Combined with the exec method, performTransformation implements the algorithm for recomputing indices and ensuring that operations remain commutative.

func (c *OTEditor) performTransformation(op *Op) {

l := len(c.Ops)

lastOp := c.Ops[l-1]

// Transformation required only when synchronizing user changes.

if lastOp.Location == LOCAL && lastOp.Location != op.Location {

if op.Index > lastOp.Index {

if lastOp.Op == DELETE {

op.Index -= 1

} else if lastOp.Op == INSERT {

op.Index += len(lastOp.Data)

}

}

}

}

We have implemented a very simple collaborative text editor. As we discussed before, one factor that we overlook in this implementation is that of establishing causality between a set of operations. The implementation, therefore, relies on the order on which the operations are received to establish consistency in the system. We will explore how these issues affect systems and how these can be resolved in my next blog post.

What’s in Part 2?

In my next post, we will review the assumptions we made in this post and see how those assumptions can be removed. We will then develop a more generalized technique for distributed operational transformation and see how we can build a better collaborative editor.