An example run of the Chandy-Lamport snapshot algorithm

In the undergrad distributed systems course I’m teaching this spring, I decided I wanted to discuss the Chandy-Lamport algorithm for snapshotting the global state of a distributed system in some detail. When I looked around to see how other people were teaching this algorithm, I kept noticing the exact same example being used in multiple people’s lecture notes, for different courses taught at different institutions.

From what I can tell, the original source of this example is Indranil Gupta’s lecture notes for his CS425 distributed systems course at Illinois. (If I’m wrong about the source, someone please let me know.) Since then, it seems like other people have been borrowing it (with attribution), and for good reason – it’s a nice example! But I found it to be a bit hard to follow, even when I watched Gupta’s own video lecture from his Coursera “Cloud Computing” course that shows him walking through the example.

Also, there’s a typo in the original example that seems to have propagated to all the other copies – they all have two events labeled “E”! So, this post is my own take on this ubiquitous example, cleaned up a bit and explained in detail. Credit goes to Indy Gupta for coming up with the example in the first place.

Introduction

A snapshot algorithm attempts to capture a coherent global state of a distributed system (for the purpose of debugging or checkpointing, for instance). This particular snapshot algorithm – the first one, as far as I know – was proposed by Mani Chandy and Leslie Lamport in their 1985 paper “Distributed Snapshots: Determining Global States of Distributed Systems”. Lamport has a funny anecdote about the paper’s origin:

The distributed snapshot algorithm described here came about when I visited Chandy, who was then at the University of Texas in Austin. He posed the problem to me over dinner, but we had both had too much wine to think about it right then. The next morning, in the shower, I came up with the solution. When I arrived at Chandy’s office, he was waiting for me with the same solution.

Getting to relate this anecdote to my class was at least half my motivation for wanting to cover the Chandy-Lamport algorithm in the first place.

Let’s jump in. We’re going to model the system we’re snapshotting as a collection of processes that can send and receive messages among themselves. Sending and receiving are events that take place on processes; in this example, there also happen to be internal events that are neither sends nor receives. Messages are sent and received along channels, which are FIFO queues going between each pair of processes. It turns out to be important that the channels have FIFO behavior for the Chandy-Lamport algorithm to work.

We’ll say that processes in our system are named \(P_1\), \(P_2\), etc., and that the channel from process \(P_i\) to process \(P_j\) is named \(C\_{ij}\). For instance, the channel from \(P_1\) to \(P_2\) is \(C\_{12}\), while the channel from \(P_2\) to \(P_1\) is \(C\_{21}\). A snapshot is a recording of the state of each process (i.e., what events have happened on it) and each channel (i.e., what messages have passed through it). The Chandy-Lamport algorithm ensures that when all these pieces are stitched together, they “make sense”: in particular, it ensures that for any event that’s recorded somewhere in the snapshot, any events that happened before that event in the distributed execution are also recorded in the snapshot.

The setup

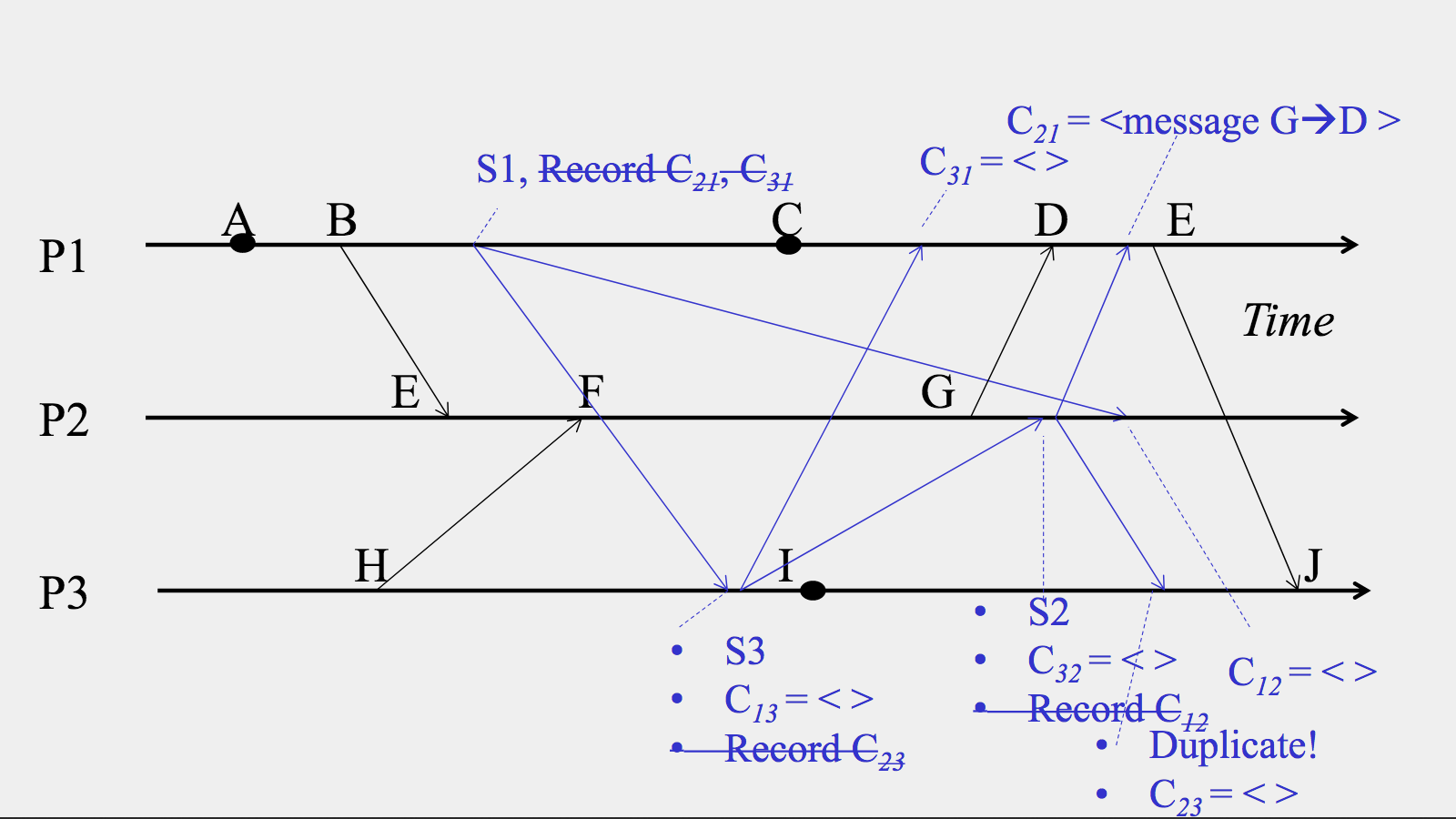

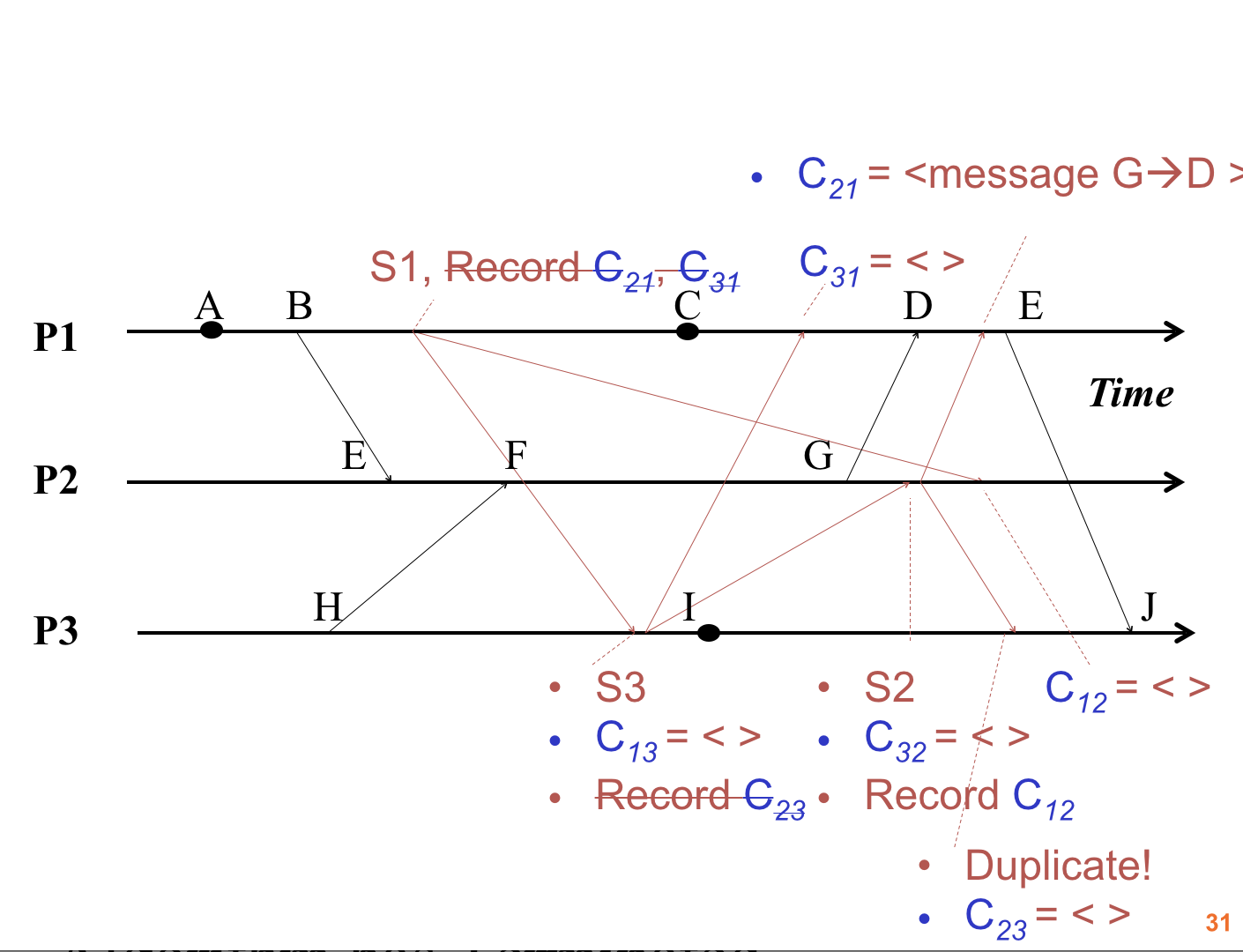

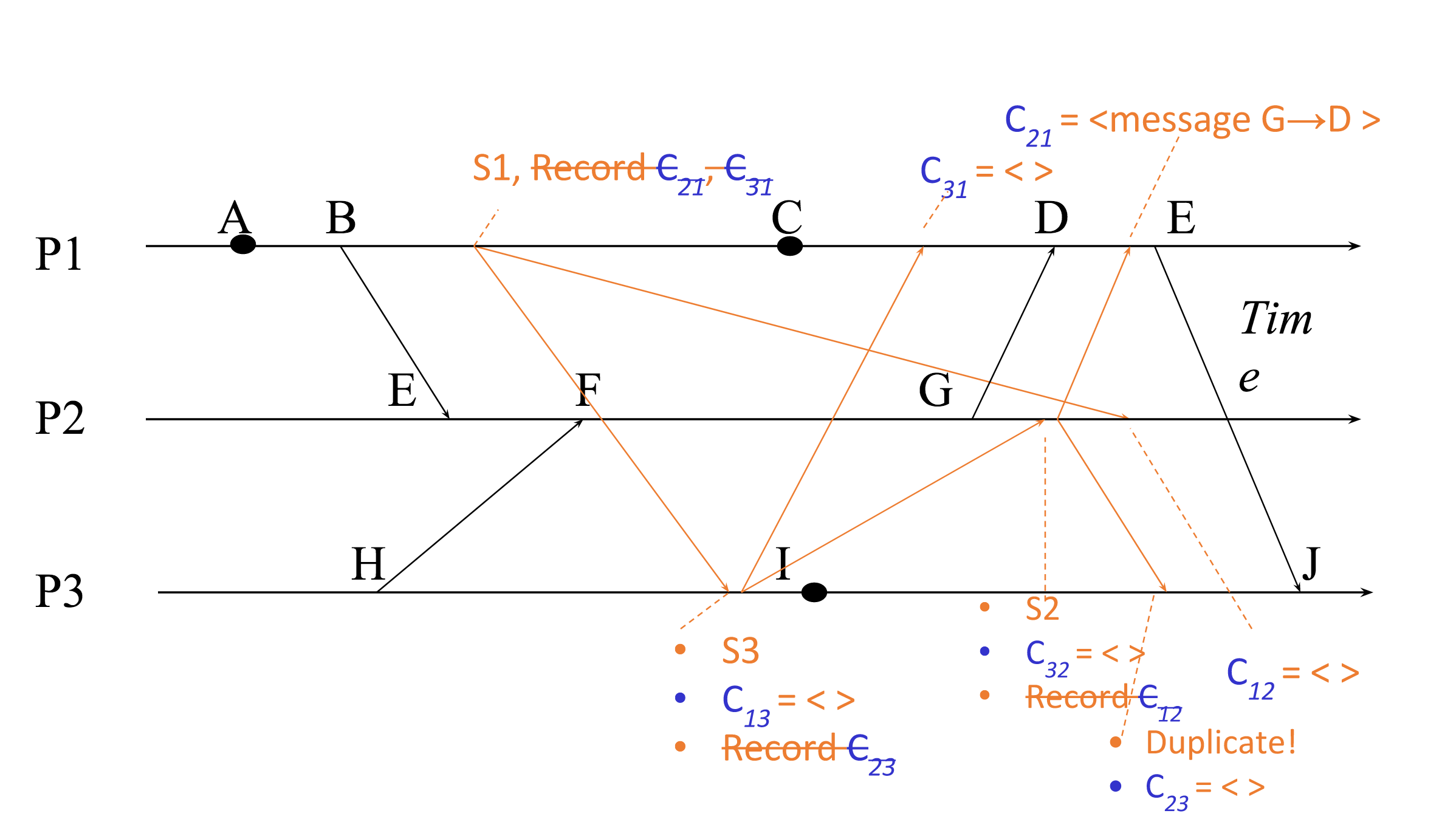

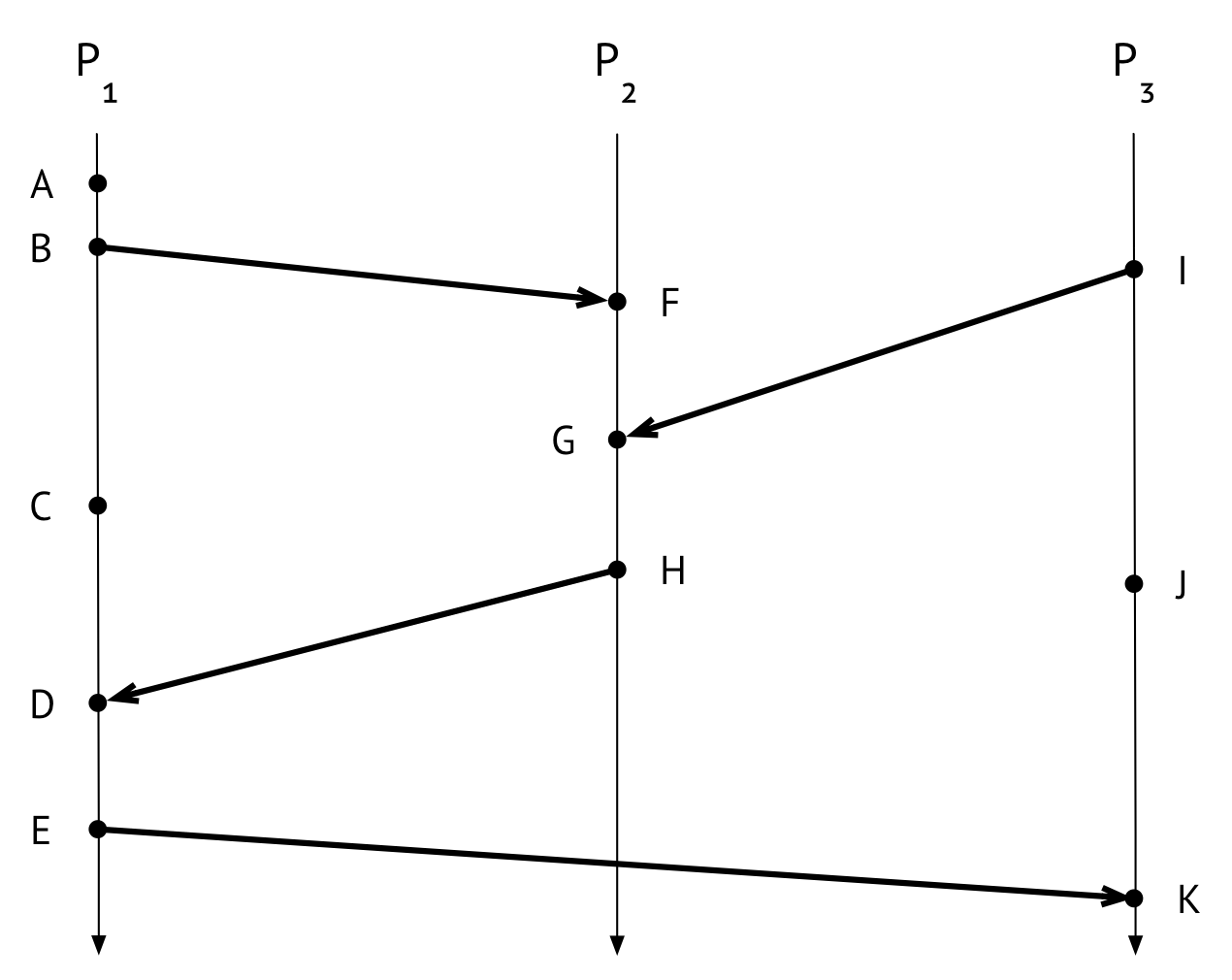

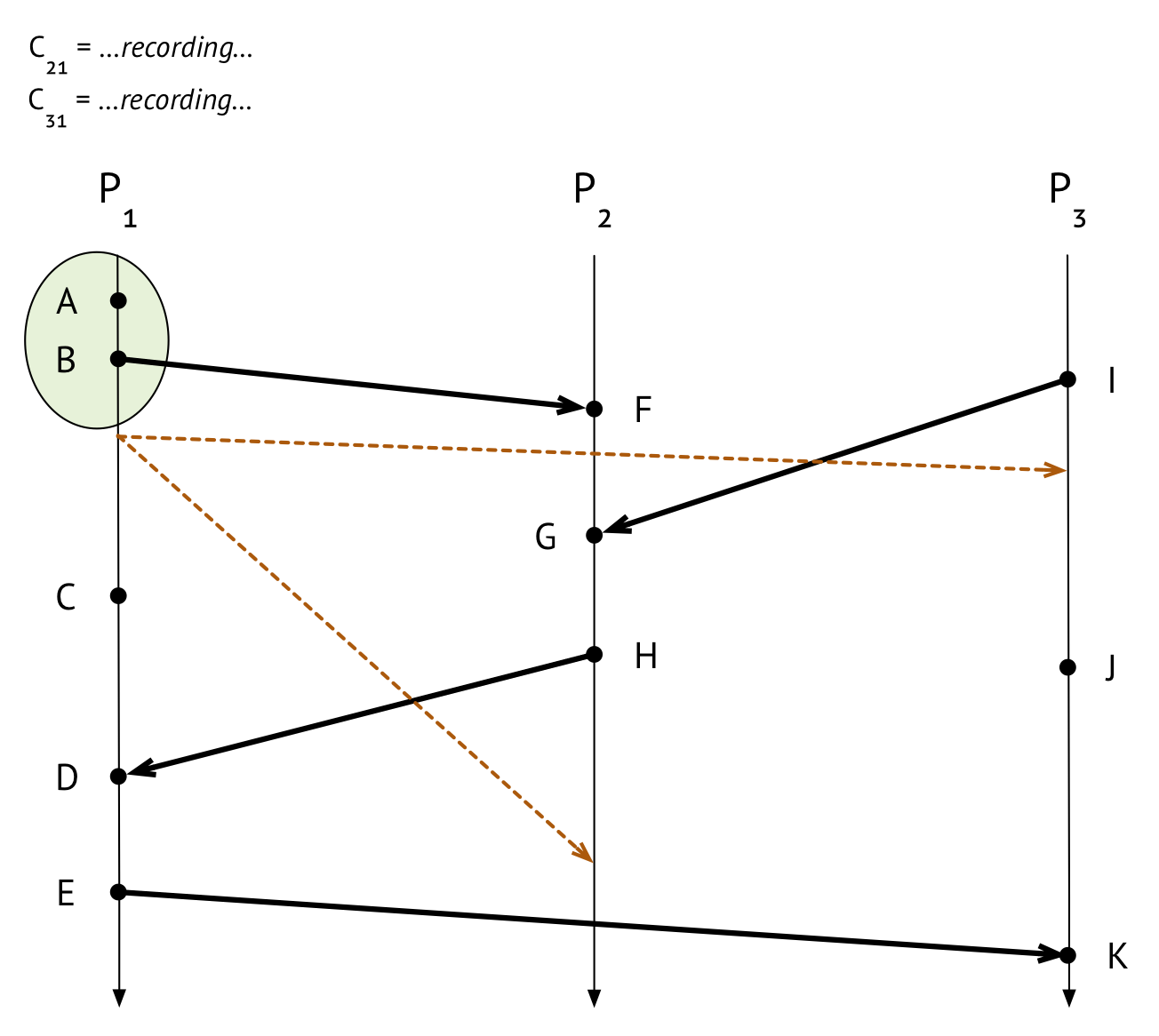

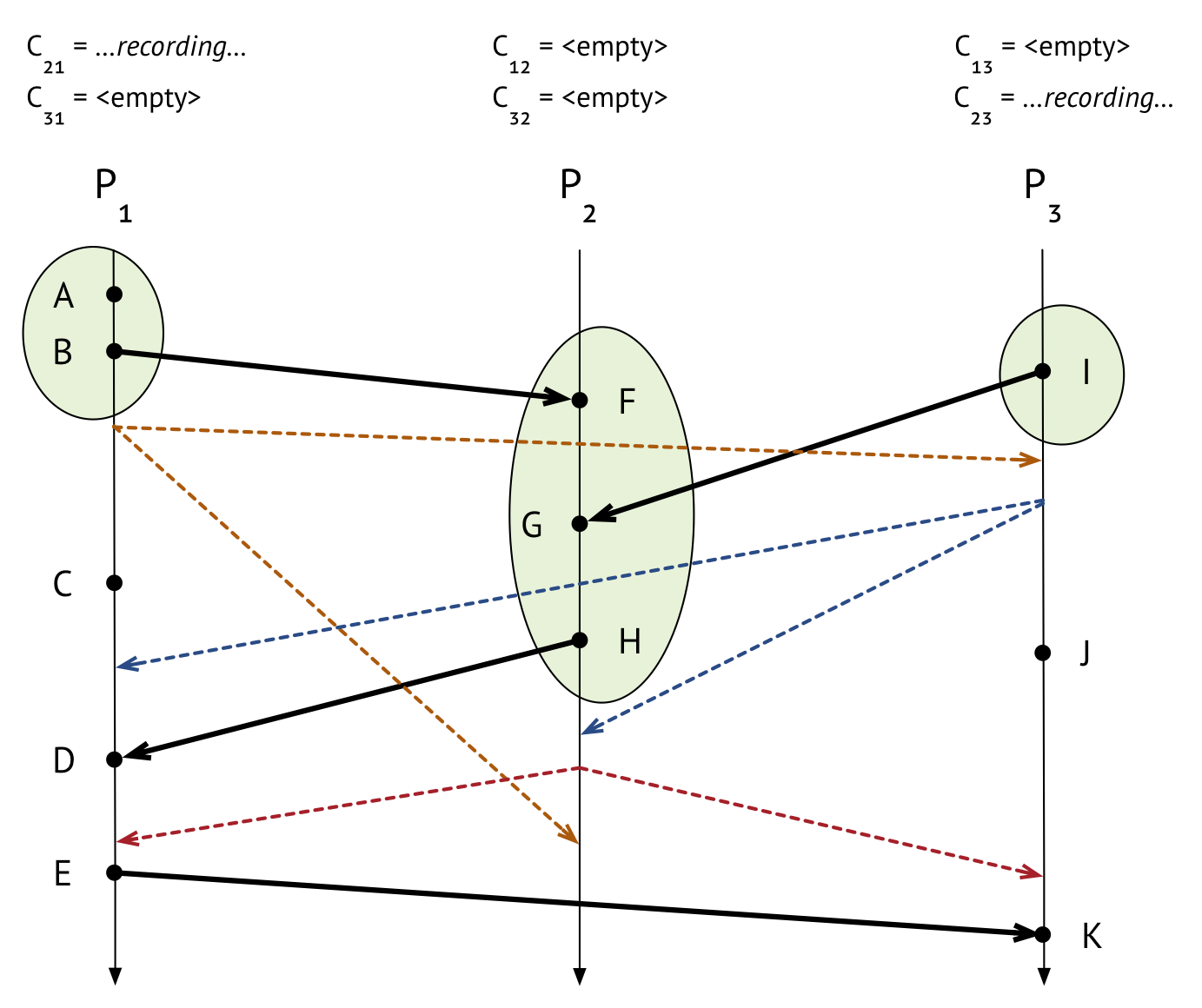

Here’s the execution we’re going to be snapshotting. There are three processes, each with several events, including messages sent and received. Dots on process lines with no incoming or outgoing arrows are internal events.

One of the especially cool things about the Chandy-Lamport algorithm is that it is decentralized – any process (or multiple processes at once!) can begin taking a snapshot without coordinating with other processes. It doesn’t cause problems to have multiple processes simultaneously begin taking a snapshot. For this example, though, we’ll say that a single process, \(P_1\), initiates the snapshot. Let’s suppose that \(P_1\) initiates the snapshot right after event \(B\) has happened.

Initiating a snapshot

To get a snapshot started, an initiating process has to do three things:

- First, it has to record its own state. Because we’re initiating the snapshot right after event \(B\), the recorded state of \(P_1\) contains the events \(A\) and \(B\). We’ll circle those events to show that they’re recorded.

- Next – immediately after recording its own state, and before it does anything else – it has to send a marker message out on each of its outgoing channels. A marker message is sent as part of the snapshot algorithm itself, as opposed to what I’ll call application messages, which are part of the system we’re taking a snapshot of. (Marker messages should not themselves be part of the state that the snapshot algorithm is trying to record; we’d like the snapshot we’re recording to not include any artifacts from the snapshot-taking process, if we can help it!) In this case, \(P_1\) sends marker messages on channels \(C\_{12}\) and \(C\_{13}\), respectively.

- Finally, it needs to start keeping track of the messages it receives on all of its incoming channels. In this case, \(P_1\) has two incoming channels, \(C\_{21}\) and \(C\_{31}\). So, \(P_1\) starts recording incoming messages on those channels.

Now, things look like this:

We’ve recorded \(P_1\)’s state, sent marker messages out along \(C\_{12}\) and \(C\_{13}\), and started recording on \(C\_{21}\) and \(C\_{31}\). We’ve drawn the marker messages as dotted lines to tell them apart from application messages.

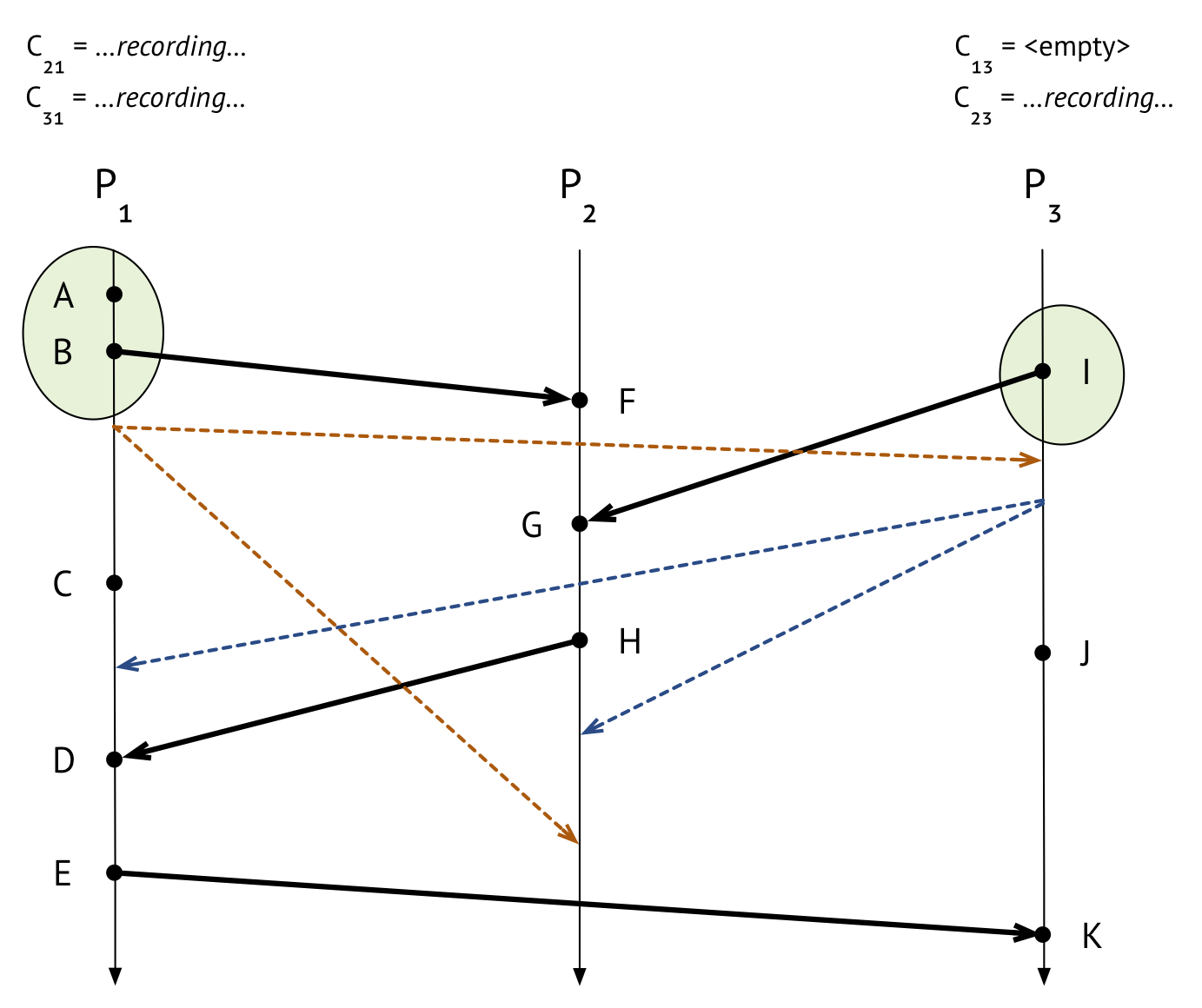

The marker message headed to \(P_2\) is taking its sweet time to get there. Meanwhile, the marker messge sent to \(P_3\) arrives pretty quickly, so let’s talk about what happens when it arrives!

Receiving a marker message: the “this is the first marker message I’ve ever seen” case

When a process \(P_i\) receives a marker message on channel \(C\_{ki}\), there are two possibilities: either this is the first marker message that \(P_i\) has ever seen, or it isn’t. If it’s the first marker message that \(P_i\) has ever seen, then \(P_i\) needs to do the following:

- Record its own state.

- Mark the channel that the marker message came in on, \(C\_{ki}\), as empty. No more messages can come in on that channel. Or, well, they can, but we won’t be recording them, and so they won’t be part of the snapshot.

- Send marker messages out itself, on all its outgoing channels.

- Start recording incoming messages on all its incoming channels except \(C\_{ki}\), the one that it just marked as empty.

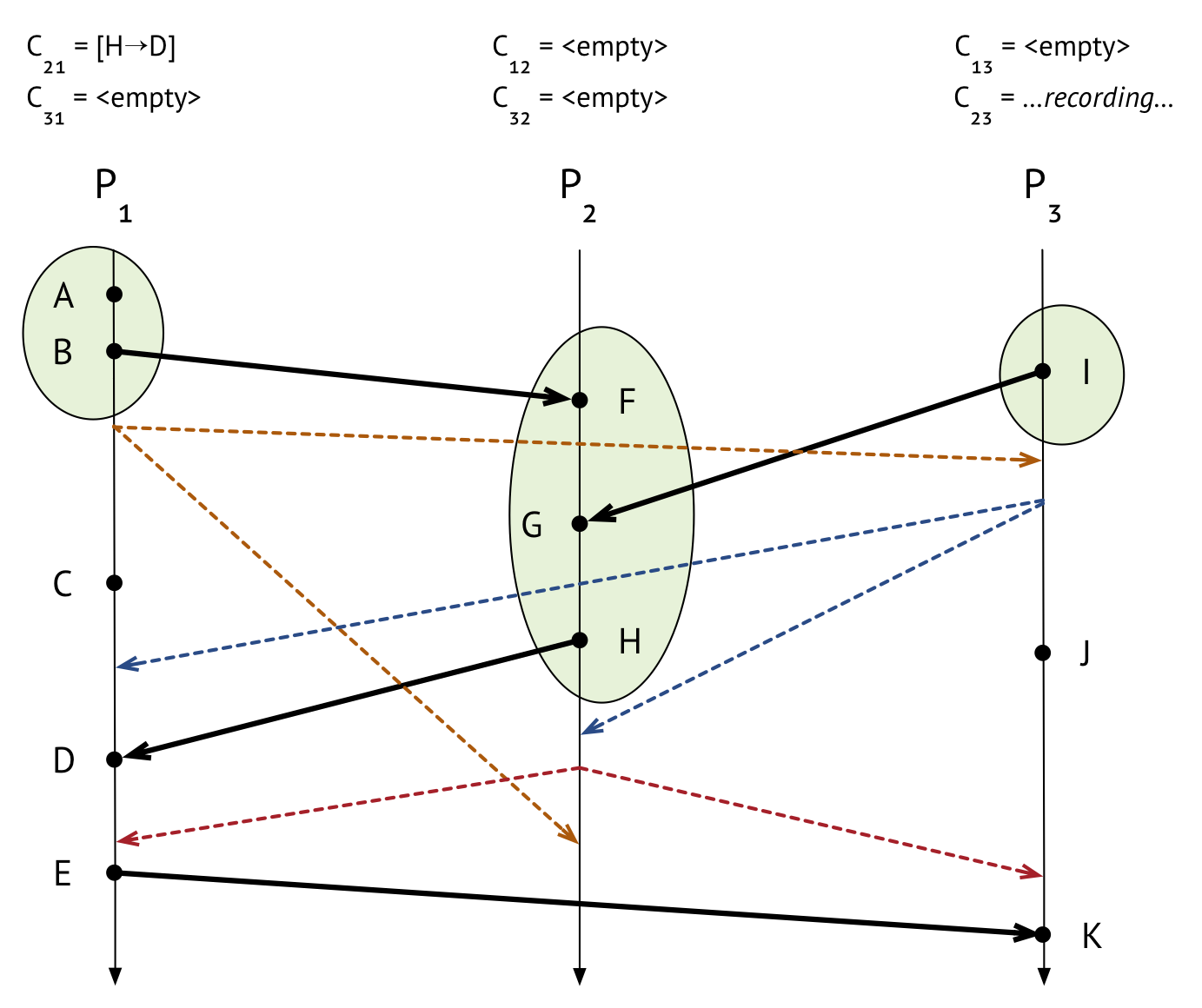

Is the marker message from \(P_1\) the first marker message that \(P_3\) has ever seen? Yes! So \(P_3\) duly follows the above steps. It records its own state, which only includes one event, \(I\). It marks channel \(C\_{13}\) as empty, because that’s the channel the marker message came in on, and it sends its own marker messages on its outgoing channels to \(P_1\) and \(P_2\). It also starts recording incoming messages on all its incoming channnels except the one it just received the marker on. Because \(P_3\) only has two incoming channels, \(C\_{13}\) and \(C\_{23}\), and it received the marker on \(C\_{13}\), it only has to start recording on \(C\_{23}\).

Now things look like this:

Yay! We’ve already recorded the states of two out of three processes! We’re on our way to being done.

Receiving a marker message: the “this ain’t my first rodeo” case

\(P_3\) has sent out its marker messages. Let’s consider the one that went to \(P_1\) first. Is this the marker message the first that \(P_1\) has seen? No, because \(P_1\) was the first process to send marker messages in the first place! (Sending a marker message counts as “seeing” one.)

Here’s what a process \(P_i\) should do when it receives a marker message on \(C\_{ki}\) that is not the first marker message it’s ever seen: it should stop recording on \(C\_{ki}\) (note that it would have started recording on \(C\_{ki}\) back when it saw its first marker message), and it should set \(C\_{ki}\)’s final state as the sequence of all the messages that arrived on \(C\_{ki}\) since recording began. That’s it!

So, \(P_1\) can now stop recording on channel \(C\_{31}\). It turns out it didn’t receive any messages on that channel during the time it was recording, anyway. So \(C\_{31}\)’s final recorded state is just the empty sequence.

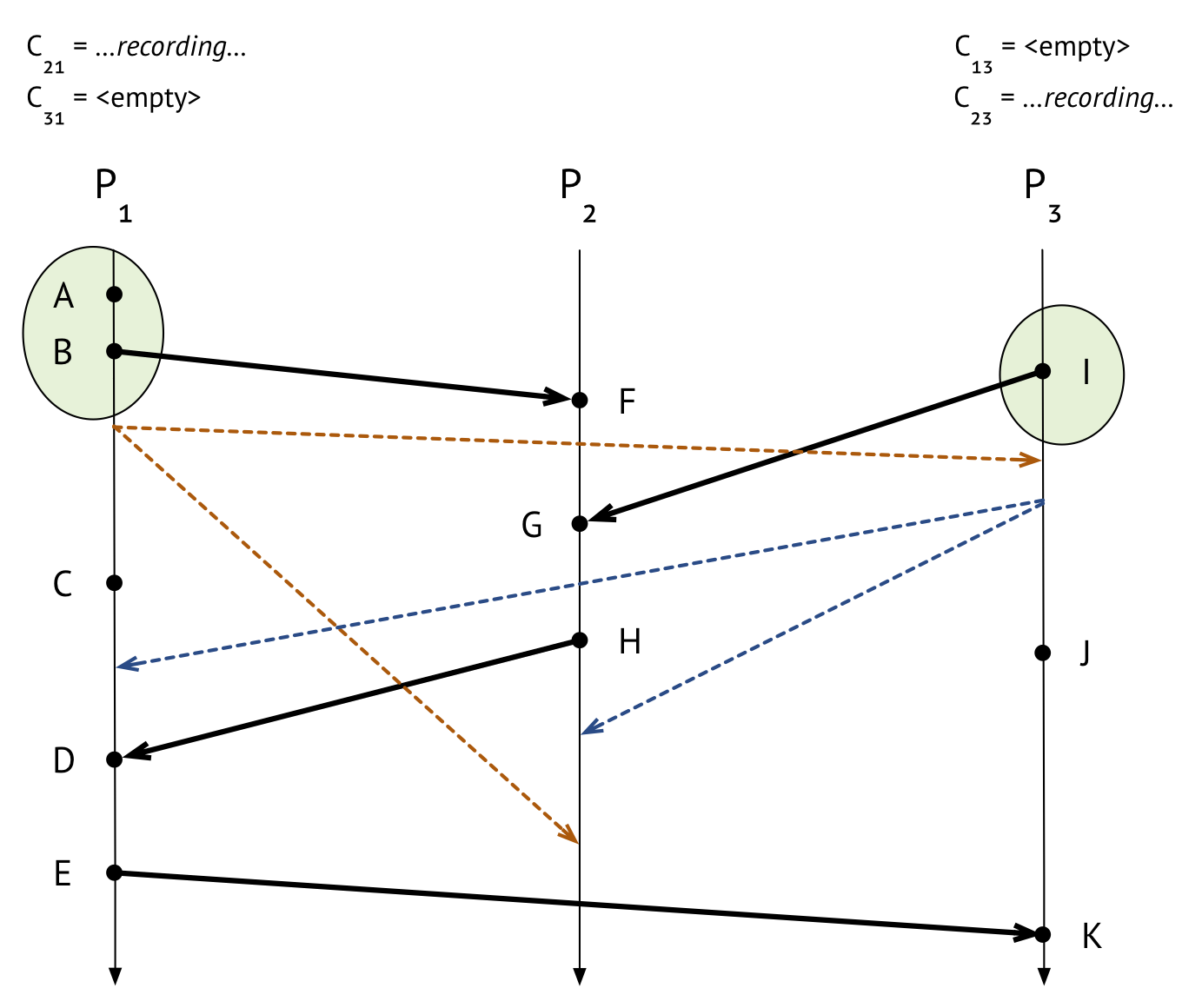

Finishing up

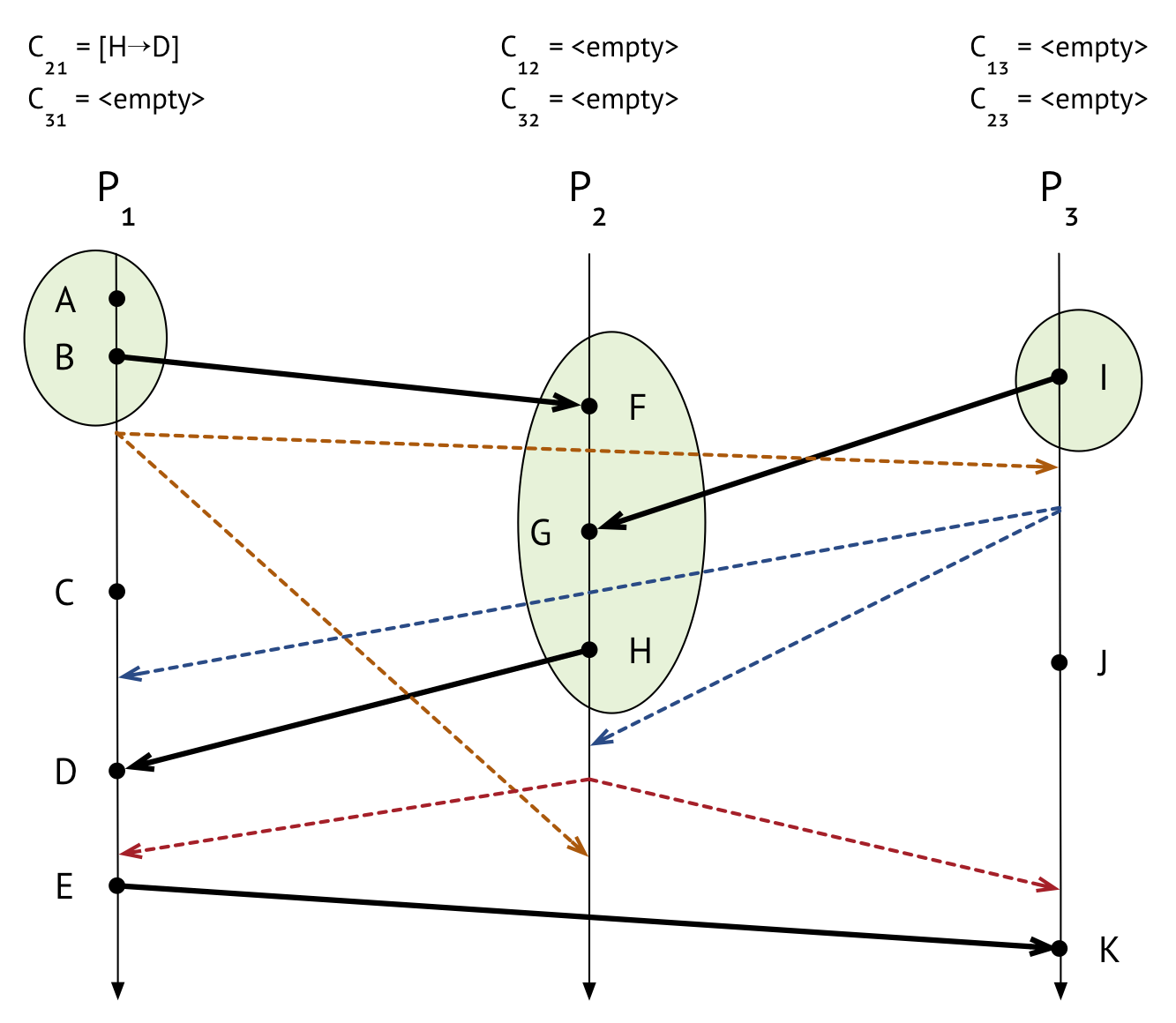

Now we can look at the marker message sent from \(P_3\) to \(P_2\). What does \(P_2\) do when it gets the marker message? It’s the first marker message that \(P_2\) has seen, so \(P_2\) records its state, which includes events \(F\), \(G\), and \(H\). It also marks the channel that the marker message came in on, \(C\_{32}\), as empty; sends out its own markers on its outgoing channels to \(P_1\) and \(P_3\); and starts recording on every incoming channel except \(C\_{32}\), the one it got the marker message on – so, just \(C\_{12}\).

Now every process has recorded its state! Our picture looks like this:

But we’re not quite done. Now that marker message that \(P_1\) sent to \(P_2\) approximately forever ago has finally arrived. Because \(P_2\) has seen a marker message before, it can now stop recording on channel \(C\_{12}\) (which it only just started recording on). No messages were received during the recording period, so \(C\_{12}\)’s final recorded state is empty, too.

\(P_2\)’s role in taking the snapshot is now completely done: it’s recorded its own state and that of both its incoming channels.

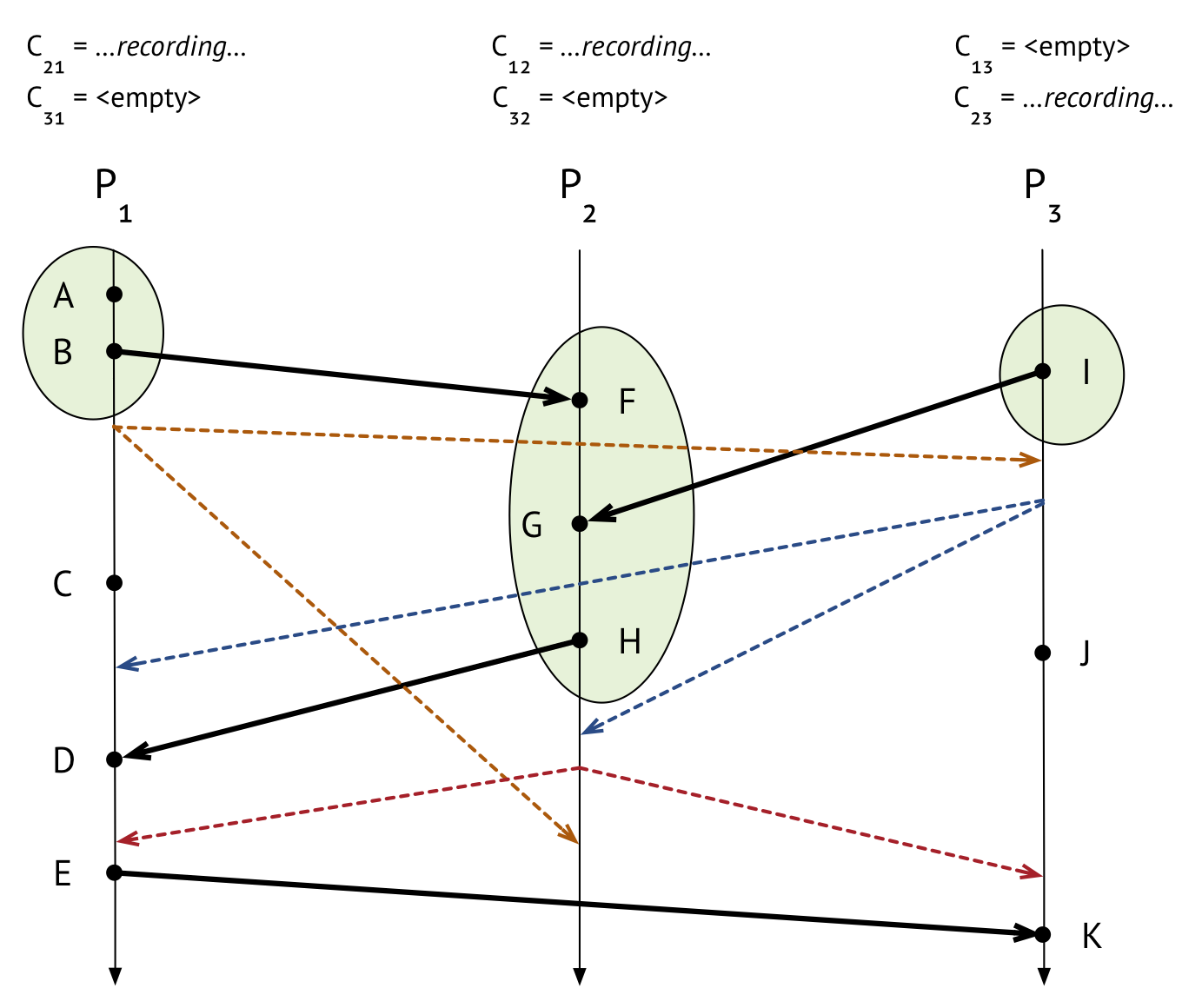

\(P_1\) still has to finish up, though. It’s waiting for a marker message to come in from \(P_2\), so it can stop recording on channel \(C\_{21}\). Hey, look – that marker message just came in!

Did any messages get recorded on \(C\_{21}\)? Yes! The message whose send event was \(H\) and whose receive event was \(D\) did. So that message goes into \(C\_{21}\)’s final channel state. (Channel recordings consist of sequences of messages, as opposed to processs recordings, which consist of sequences of events.)

And finally, \(P_3\) gets the last marker that it was waiting for, from \(P_2\), and the final state of \(C\_{23}\) can be set to empty because no messages came in while we were recording on that channel.

Now, all the processes’ states and all the channels’ states have been recorded, so we can say that we’re done!

Discussion

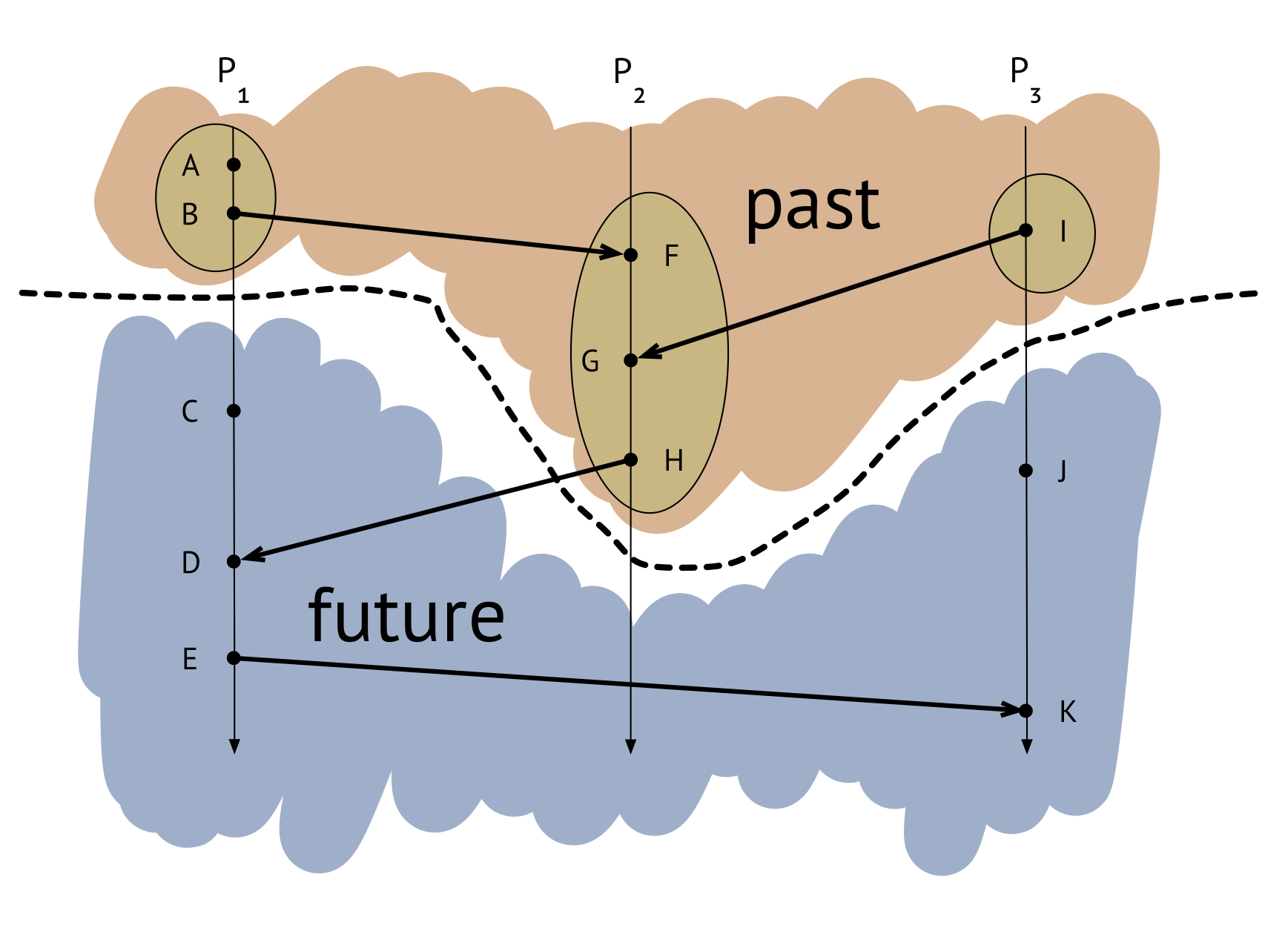

Now that we’re done taking the snapshot, we can ignore the marker messages and just look at the state we recorded. We said earlier that a property we want to have be true of any snapshot we take is that, for any event recorded somewhere in the snapshot, any events that happened before that event in the distributed execution should also be recorded in the snapshot.

We can see that that’s true of the snapshot we just took: for every circled event, if we look at the events in its causal history, those events are all in the snapshot as well. In other words, the snapshot produces a consistent cut in our diagram, where every message received on the “past” side of the cut was sent on the “past” side, and no messages go backwards in time.

A student asked me whether event \(D\) counts as part of the recorded state, because it’s the receive event for the message from \(H\) to \(D\) that we recorded on \(C\_{21}\). We should not consider \(D\) to be part of the recorded process state. (In fact, in our example we have event \(C\) hanging out on \(P_1\) in \(D\)’s causal history, so if \(D\) were in the snapshot, then \(C\) would have to be as well for it to be a consistent snapshot.)

So, what’s the point of recording channel states, then? Well, imagine that we want at most one process in this execution to have exclusive access to some sort of resource (say, a file). We can think of access to the resource as being a token that processes pass around. At any given time, either a process should have the token, or it should be in transit between processes.

Suppose that \(P_2\) has the token and then decides to hand it off to \(P_1\). The message sent at \(H\) and received at \(D\) might say, “I’m passing the token to you.” If this were the case, then the process state at \(P_2\) was recorded after \(P_2\) gave up the token, but the process state at \(P_1\) was recorded before \(P_1\) got the token. This isn’t great – it means that, for anyone looking at only the recorded process states, the token seems to have disappeared! Recording the channel states addresses this problem: since the message from \(H\) to \(D\) is part of the recorded channel state, someone looking at the snapshot can inspect the contents of the message and see that when the snapshot was taken, the token was in transit from \(P_2\) to \(P_1\), maintaining the invariant that there should be one token in the system.

Comments